COLLINSVILLE — Elizabeth Barrientos went through DeKalb County Schools in northern Alabama as a native Spanish speaker.

Born in Gadsden, Barrientos and her family have been in Collinsville for about 30 years after moving there from Mexico. She has an older sister and two younger brothers, and her parents work at a local chicken farm.

“Back then, my parents viewed English as a success here in the States. I had to learn it quick,” Barrientos, 26, said in a December interview. “There were times where we would have to go with them to a doctor and we were the ones translating for them. We were little, we only knew some terminology.”

Now she teaches English as a second language at the same school she attended as a child. Barrientos is an English Language (EL) teacher at Collinsville High School, a rural public K-12 school part of the DeKalb County School system.

She started as a teacher’s aide while she was in high school in 2018, and continued to do that while she got a degree in early childhood education at Jacksonville State University. In the spring of 2024, Barrientos covered another EL teacher’s leave, then was hired full time to teach first through third grade.

About 22% of DeKalb County Schools’ students are English Language Learners (ELL), but Crossville and Collinsville high schools have more than double the district’s ELL students. According to district data, Collinsville’s student population is 66.6% Hispanic/Latino and 42.8% ELL. Over 90% of Crossville’s student population is Hispanic and nearly 57% are English Language Learners.

She said in a December interview that her experience in the school system helps her connect with her students.

“We have so many things in common,” she said. “They’re able to tell me, ‘Hey, I’m not understanding this. Can you please help me?’ Whereas, if they don’t have that comfort or build that relationship with you, I feel like they’re not able to tell you.”

The school system has the third highest percentage of ELL students in the state, behind Albertville City School (37.49%) and Decatur City Schools (23.36%), according to data from the Alabama State Department of Education.

“I still teach the same curriculum that they are doing, with ELLs I don’t translate it because the teacher won’t always translate it for them,” she said. “If there are some things that they’re not quite understanding, then I will tell them in Spanish.”

Because of its significant ELL student population, DeKalb County will get an additional $1.4 million in its fiscal year 2026 budget from the RAISE Act. According to Anna Hairston, the school system’s director of federal programs, the system’s total budget for FY26 is $124.8 million.

Since FY17, the state has increased its investment in ELL students from $2.7 million to $37.5 million in FY26 through both headcount-based funding and the creation of the RAISE Act, which allocates additional funds to public schools based on weights. While Alabama’s Hispanic and Latino population has remained around 5%, that demographic accounted for about a third of the state’s population growth between 2010 and 2020, according to a 2023 analysis by Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama (PARCA).

Barrientos and other teachers in the DeKalb County system have to navigate their teaching responsibilities amidst increased U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations in the area.

Hairston and Brown planned for a few parents to be interviewed during the August school visit, but ICE appeared in the county and arrested about 15 people. The parents Hairston and Brown picked out were U.S. citizens.

“This has really gotten our parents on edge, so we just steered away from that and hope to stick to the education side,” Hairston said.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Attempts to reach the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) were unsuccessful.

Hairston said in recent correspondence that similar operations had increased in the last six months and said parents would be hesitant to agree to their children’s faces being visible in photos.

“A lot of them are scared with everything,” Barrientos said in December of concerns she hears from her students. “They’re just going to work, and a lot of them are being taken.”

Growing proficiency

Collinsville High School significantly improved in English language proficiency among ELL students from the 2023-24 school year at 25.82% to 40.86% proficient in the 2024-25 school year, according to state data.

Crossville’s state data is separated into high, middle and elementary school, and not all Hispanic students are in the ELL program, especially in high school. However, Crossville Elementary School saw a similar trend to Collinsville’s proficiency. In the 2024-25 school year, 40.45% of ELL students were considered proficient in the English language, up from 13.46% in the 2023-24 school year.

For EL teachers, there are three primary methods of instruction, said Erin Brown, one of the school system’s language acquisition coaches, during an August visit to the school system: traditional classes, “push in” and “pull out.” Depending on what teachers need, Barrientos will push in or pull out, she said in December.

For the push in method, Hairston said in a December interview that EL teachers like Barrientos will come into a class that ELL students are mixed in with native English speakers and integrate instruction in small groups.

“They’re still in that classroom. They’re still able to use their classroom resources. And they will do additional lessons,” Hairston said.

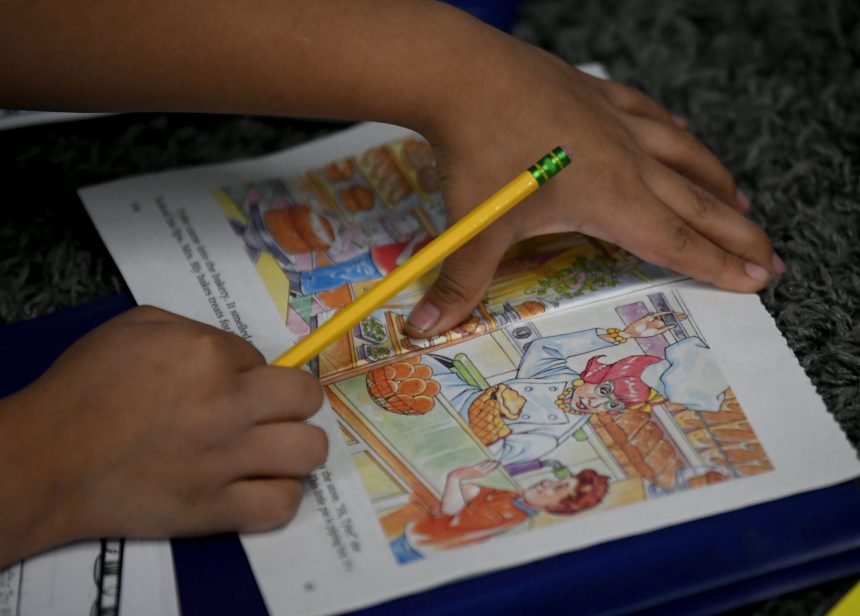

That is the method Barrientos used during an August visit in second grade teacher Laura Smith’s classroom. The class was split into three groups of about four students and had ELL students and native English speakers. Barrientos was working with a group of ELL students on the floor.

“There is an EL teacher that pushes in, as well as an auxiliary EL teacher on specific days. So they accommodate and or translate if needed, but their instruction is given in English,” Brown said.

The pull out model involves small groups of students leaving a classroom and visiting another teacher. Tanya Ford, a fourth and fifth grade teacher, has a small group of students visit her makeshift classroom in a trailer for 20-30 minutes throughout the day.

“I’m using lessons that are geared towards where their deficiencies are. So they’re kind of levelized math-wise, but they may not be exactly level in language development,” Ford said.

During the visit, Ford gave the students a number which they had to break down into 100s, 10s, 5s, and 1s, with pieces of plastic. One of the students was a “newcomer” and did not know very much English. He got the breakdown wrong. Another student who understood English better helped him fix his answer by communicating with him in a mix of Spanish and English.

“He came late second grade, and he’s still kind of limited. He had prior schooling in Guatemala, so he’s actually pretty smart. He’s just just struggling with the language,” Ford said. “That’s pretty much why. He was listening to me say the numbers, but he didn’t catch it.”

At Crossville High School, another K-12 school that is 11 miles and about 15 minutes through the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains from Collinsville High School, Phillip Mosley, an EL teacher, demonstrated the push in method in an 11th grade class during the August visit.

Katie Williams, another EL teacher at Crossville, had about 15 11th graders in her class one day early in the school year. She was teaching them opposites, and Mosley helped.

“¿Es un gato?” Mosley asked the class.

“¡Perro, sí!” he said when a student showed him their whiteboard with the answer. “Bueno.”

Crossville has 15 EL teachers and six auxiliary EL teachers, Hairston said. When Hairston started as an EL teacher in 2004, she was one of two.

“We’ve been able to utilize those funds to put more support and for the kids who we believe need it the most,” Hairston said of the RAISE Act funds.

According to data from the Alabama State Department of Education (ALSDE), 39.76% of ELL students at DeKalb County were considered “proficient” in the English language in the 2024-25 school year. That is a slight improvement district-wide from the 2023-24 school year where 25.82% of ELL students were considered proficient.

Smaller classes and groups like those at Crossville and Collinsville help EL students understand the English language, but that’s not all EL teachers do for their students.

Dreams of service, fears of ICE

Mosley has taught for the last five years at Crossville High School as an English language teacher. Instruction is one part of his job. So is building trust and establishing relationships with the families of his students.

“If they’re a new kid into our system, or a new kid into the United States, the first person they see once they get registered is me,” Mosley said. “I meet with them. I meet with their parents. At that point in time, I stay in communication with their parents throughout their entire schooling from ninth grade until they graduate and in many cases, after they graduate.”

Those relationships, he said, are the only way for the EL students to have a successful education. Those relationships help, especially now that he is starting to get siblings of his first students, like Maria Tovar Garcia.

Tovar Garcia moved to the United States from Guanajuato, Mexico, two years ago. Mosley said her parents applied for and got their family’s citizenship before they moved. Maria said she loves Crossville, but still misses home sometimes.

“It was hard. I miss my friends and my family that still live there,” Tovar Garcia said.

Her brother, Jose, graduated from Crossville High School last year and is currently working, but he wants to join the U.S. Marine Corps. Her father works in construction and her mother on local farms.

Beyond teaching his students how to speak English, Mosley and other school administrators help families get settled in DeKalb County. One of Mosley’s former students, who came to the United States without legal status, was the smartest student in his classroom, he said, and is now a citizen and an immigration lawyer.

“She’s been here over the last three years to discuss new laws and to discuss those,” Mosley said. “She comes in and she meets with them on an individual basis just to let them know what things affect them. Most of them, their biggest concerns are their family. We’re very fortunate with that.”

He said that five of his students since he started at Crossville have gotten their citizenship through that former student. Most of his students, though, have legal status.

“That’s one thing that I think we really pride ourselves on in DeKalb County, is helping families and students find resources, whatever those may be, whether it be food, beds, clothing,” Hairston said.

Barrientos said in December that growing up in DeKalb County and honoring her Mexican culture allows her to teach them more effectively. She is currently enrolled in a masters program at the University of Alabama in Huntsville to get a Master of Education degree, English Speakers of Other Languages Concentration.

“I always thought I want to be someone that pulls a group or something, and being an EL, has really shown me this is my calling,” she said. “I’ll be able to help more kids and reach more people and their parents.”

She said that sometimes her students will ask her questions about immigration, and through those conversations she realized that she has a lot in common with her students even though she was born in the U.S.

“It really is hard that some people see us as different or less than them. At least speaking for myself and my family, we just want to make this a better place. We do want to continue our culture,” she said. “They’re always talking about skin. Don’t forget your culture. Don’t be scared to show who you are.”