Shawn Rushing said it was “exciting” to hear about a plan for improvements and upgrades across Houston ISD, which is holding a series of community meetings to discuss a $4.4 billion bond proposal that could be placed on the ballot for a vote in November.

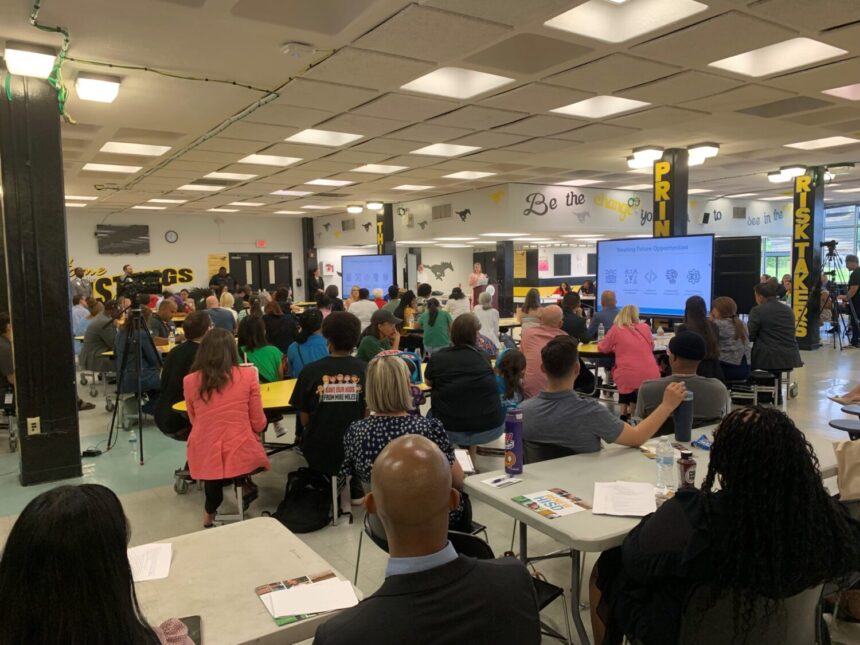

The Madison High School graduate, whose children also attended HISD schools, was among the community members who crowded the Fondren Middle School cafeteria Tuesday night to hear specifics about the plan. District leaders want to renovate and in some cases rebuild aging campuses while also bolstering safety, security and technology and expanding HISD’s pre-kindergarten and career training programs.

But at the end of the district’s tumultuous first year under state-appointed leadership, which has overhauled curriculum, made widespread staffing cuts in anticipation of a budget deficit and forced out popular principals and teachers over their performance, Rushing said she was not sure whether she would vote for it.

“When you look at the presentation, who wouldn’t want all these wonderful things for children?” she said. “But we have to be able to trust that it happens.”

“Trust” was a term used frequently Tuesday night, when some other community members said they would vote against what would be HISD’s first bond proposal since 2012. It also would be the largest school bond package in Texas history – a year after the state’s largest school district was taken over by state officials.

Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath replaced HISD’s nine elected trustees with a board of managers and installed Mike Miles as superintendent, intervening because Wheatley High School had a string of failing academic ratings from the state. Sweeping changes have ensued, and community members and local elected officials have pushed back by staging protests and calling for investigations by both state and federal agencies.

Tiffany Hogue, the mother of an HISD high school student and two middle school students, called it “tone deaf” for district leaders to seek support for a bond and said she would not vote for it. The board of managers has yet to decide whether to place the measure on the November ballot.

“We saw tonight that there’s what, a decade of deferred maintenance? We really should have already had two or three bonds at this point,” Hogue said. “There are lots of needs in our facilities, so I think everyone wants to support it.

“But in the current context and current climate,” she added, “when Superintendent Miles and an unelected board of managers have spent a year disregarding what parents have said to them, what teachers have said to them, what students have said to them, I think that’s a really hard sell.”

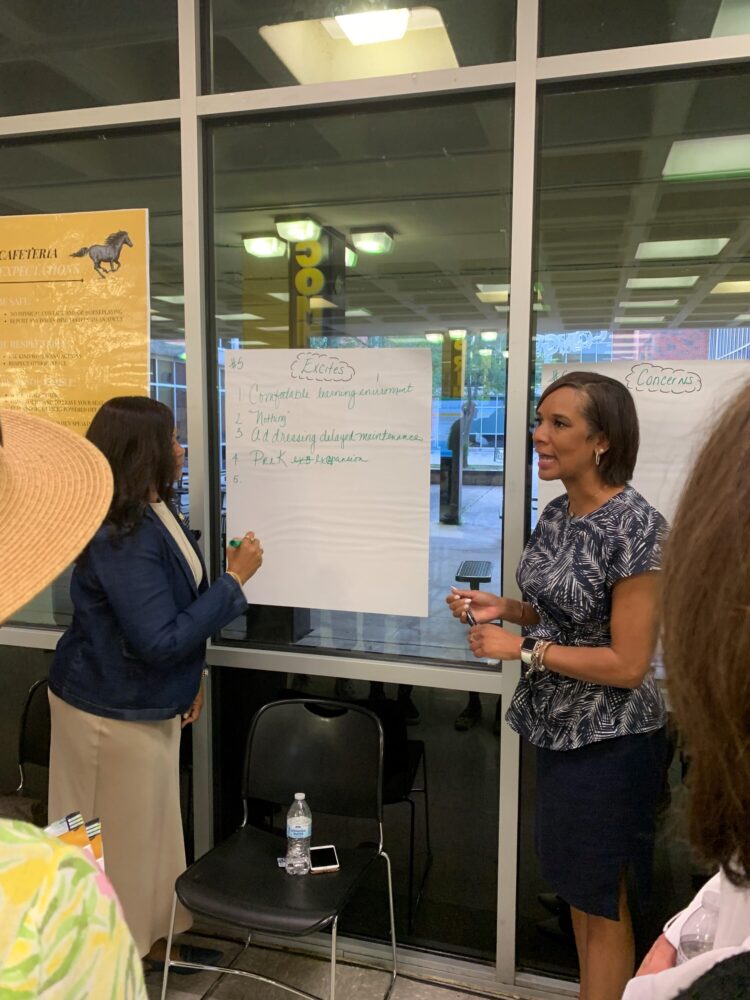

Tuesday’s community meeting, like the ones scheduled for 6-8 p.m. Wednesday at Fleming Middle School and 6-8 p.m. Monday at Forest Brook Middle School, featured HISD administrators discussing the bond package while fielding questions from the district’s Community Advisory Committee, which is charged with driving engagement among the public.

Committee members pressed the district administrators for more data supporting the proposal and also for more details, such as how many students currently are taught in temporary buildings and which campuses would be prioritized for renovations. Some also wondered if HISD is considering closing underutilized schools and consolidating campuses since the district faces a budget deficit in excess of $500 million while having seen an enrollment decline of more than 20,000 students in recent years.

Alishia Jolivette, HISD’s interim chief operating officer, said district leaders plan to address that next year.

“That’s a conversation that HISD has kicked the can down the road,” said advisory committee co-chair Judith Cruz, a former HISD trustee. “I started on the board in 2020 and we started those conversations, and for myriads of reasons, we have never addressed that looming problem, and it’s going to continue to be a problem.”

Still, both Cruz and fellow co-chair Scott McClelland, a former president for Texas grocery store chain H-E-B, signaled support for a bond. Cruz said there would be no other feasible way to pay for widespread facility upgrades in HISD, where some schools have malfunctioning air-conditioning and heating systems and some were damaged by the deadly windstorm that swept through the region on May 16.

McClelland urged community members to look beyond current district leadership and focus on the long-term needs of HISD and the families it serves, noting that investments made through a bond have little to do with curriculum and would outlast the tenures of Miles and the board of managers.

“Is every kid going to be safe?” McClelland said. “Is every kid going to be able to go into a classroom where it’s not 90 degrees or 50 degrees? Is every kid going to have access to good water? Will there be remaining remediation of mold? Because as a parent, I wouldn’t want that.

“So in my mind, it really doesn’t matter if you like Mike Miles or you don’t like Mike Miles,” he added. “It’s really a question of, as you get to the students, is what’s the environment that you would accept for them?”

Linda Scurlock, a retired teacher who worked at three different HISD schools from 1970-2006, acknowledged the needs in the district but questioned whether the $4.4 billion would be well-spent.

So did John Godchaux, the father of an HISD elementary school student. He said he attended Tuesday’s meeting as a concerned parent and also because he wanted to learn more about the bond proposal, adding that he came away dissatisfied over what he called a “shocking lack of detail” and inadequate responses to the questions posted by members of the community advisory committee.

“The main elephant in the room is the leadership of HISD, which I don’t think can be trusted with a huge amount of money,” Godchaux said. “Four billion dollars seems like a lot of money to hand to an unaccountable, unelected board and supervisor.”