The Boston Globe

Many of these dead zones overlap with vulnerable communities — already poorer, sicker, and less well-resourced than the rest of the state. Where do patients go?

For years, Donna Adams could glide from her Nubian Square apartment to the Walgreens on Washington Street in her electric wheelchair. It was so close, she said, that “in the wintertime, you didn’t even need a coat.”

Now in her 70s, Adams takes the bus another 20 minutes to a Walgreens on Columbus Avenue, enduring further strain on her aging joints.

“It’s not convenient,” she said. “And it’s not acceptable.”

More than a protest, it was a cry for help — one that echoed across Massachusetts, to little avail.

Since 2017, at least 26 pharmacies have closed in Boston, and about 200 shuttered statewide, according to data from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. State estimates show that a comparable number have since opened, though they rarely serve the same communities.

Often left behind are so-called pharmacy deserts, pockets of the city where the majority of residents live at least a half-mile from the nearest drugstore, and lack cars to make the trip. A Globe analysis found that almost 15,000 people in Boston live in such deserts, without a reliable place to go for prescriptions, over-the-counter treatments, and medical advice. Many of these dead zones overlap with vulnerable communities — already poorer, sicker, and less well resourced than the rest of the state.

Roxbury is one such victim. Having lost four drugstores since 2017, the vast majority of the neighborhood now qualifies as a pharmacy desert. Half of East Boston and Dorchester are similarly underserved. Zoom out, and the problem persists well beyond the city: Much of Brockton is a desert, as are sizable chunks of Everett, Revere, and Lawrence — home to large Black, Latino, immigrant, and low-income populations.

A host of reasons are to blame for drugstore closures, from the tricky economics of dispensing medications to profit-and-loss decisions made in corporate boardrooms hundreds of miles away.

In statements, corporations fault increased competition, changing consumer behavior, staffing shortages, or simply a shift in corporate thinking about how many physical stores make sense financially, and where they should be located. Concerns over shoplifting and the comedown from pandemic sales of vaccines, at-home test kits, and masks — plus the billions drugstores owe in settlements from contentious opioid lawsuits — scarcely help.

The business of selling pharmaceuticals has also changed markedly since the turn of the century amid the rise of pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs. These powerful intermediaries negotiate drug prices on behalf of employers and insurers. But a growing tide of research shows that PBMs take a sizable bite of prescription profits for themselves and squeeze pharmacies in the process, forcing some of them out of business.

In Massachusetts, half of the recently shuttered pharmacies belong to the three major corporations, which plan on closing hundreds more nationwide in the next few years.

Rite Aid ignited the wave with 33 pharmacies gone in 2018 and 2019. Walgreens followed suit with two dozen closures of its own. CVS, too, has eliminated eight drugstores in Boston from Beacon Hill to Dorchester since the pandemic began as part of its plan to reduce locations. In the meantime, only two CVS locations have opened here — on the ground floor of a luxury apartment building in wealthy Brookline and another a block from Boston Common, state data shows.

The disappearance of drugstores creates craters of inaccessibility in places that often need pharmacy access the most, said Bisola Ojikutu, executive director of the Boston Public Health Commission.

“These closures are reinforcing systemic inequities and long histories of structural racism,” she added. “It’s a significant concern for the city and the health of our people.”

Poorer neighborhoods already grapple with higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, and asthma. So much so that the average life expectancy in Roxbury is 68, 23 years fewer than in Back Bay.

In Nubian Square, where many residents are Black, low income, and without access to a car, the nearest pharmacy is more than a mile away. But many white and well-off residents in Back Bay can walk to two or three pharmacies within a half-mile. The neighborhood has three times as many pharmacies per capita as Roxbury.

More pharmacy closures will only further constrict access to flu vaccines, diagnostic tests, and emergency medications, such as naloxone, used to reverse opioid overdose, said Elaine O. Nsoesie, a professor of global health at Boston University. Studies show that after a drugstore shutters, people are less likely to take medications for heart disease, the leading cause of death among Americans of all races. Black people, who studies show are most likely to die from the illness, are the most burdened.

“If people stop taking their medications as they are supposed to, it’s sometimes hard for them to get back on track,” Nsoesie said. “It makes solving the gaps in our communities even harder.”

A shuttered pharmacy, then, is a symbol of forgotten people, a message that underserved neighborhoods do not matter much to those in power, said Louis Elisa, former president of the Boston chapter of the NAACP.

“It is not about soaps or sponges. One day, you’re going to do your business, picking up what you need, when you need it,” Elisa said. “The next minute, the pharmacy is not there, another sign of how little attention our communities are sometimes given.”

Shuttered Walgreens, CVS stores leave patients stranded

The center was well lit and welcoming, with a brightly decorated bulletin board masking the uncertainty patients felt about how they would keep up with their needs for prescription medicine. Over the hum of dialysis machines, staffers brainstormed alternatives to the drugstore for those who had relied on it.

Scott herself frequently journeys from the South End to Fresenius for dialysis appointments, a life-saving treatment she cannot go without. Her brother used to stop by the pharmacy and drop off her other medications, until he left Boston. So she added a Walgreens prescription pickup into her dialysis trips. Then it closed. “Now I don’t have anybody,” Scott said.

She does not drive and cannot rely on her remaining relatives to fetch her medication. Above her protective cloth mask, her eyes and brows conveyed her frustration.

“What am I going to do?” she asked.

No one has the answer — lawmakers included. Public officials in several states, including Maine and West Virginia, have created new regulatory structures to oversee how insurers price drugs and how providers spend revenue they earn from prescriptions. The same cannot be said for Beacon Hill, where dozens of bills to change the pharmacy landscape have yet to pass.

House representatives unanimously approved an oversight bill to regulate the industry more closely on Wednesday, leaving the Senate to reach an agreement on the matter before the end of legislative session next week.

Segun Idowu, chief of economic opportunity and inclusion, has mulled the idea of filling vacant pharmacy properties with co-ops, where the entrepreneurs — businesses that meet a health need, like a pharmacy — manage and own a piece of the space where they operate. Maybe, the city could even find grant money for independent pharmacies, so they can lean on an extra income source that is separate from drug sales, he said.

Right now, the shuttering of drugstores “is just what it’s going to be for the foreseeable future,” Idowu added.

Some chain pharmacies say they already account for the impact on communities when deciding which locations to close.

“The vast majority of the stores we’ve closed to date do not include stores in communities with a SVI rating (i.e. the most vulnerable),” CVS Health spokesperson Michael DeAngelis said in an email. “When we do close a store, we ensure there are other nearby pharmacy options. Often, it is another CVS location.”

The company is fully aware of the special importance of pharmacies in communities of color. It released a report in January, saying that Black and brown people visit local pharmacies in-person for basic health services, such as immunizations and diagnostic tests, more than white consumers do. Yet a sizable share of the stores the chain has closed served these very neighborhoods. (A CVS storefront in a Dorchester Target shuttered in March, after locations in Brockton and Lawrence closed two years ago.)

“They opened a Foot Locker instead,” Harris said.

How pharmacy benefit managers shift the drugstore landscape

Nunzio Celano can still taste the chilled delights of the soda counter and feel the warmth of the “medicine man” behind the window at two independent drugstores he lived near during childhood in East Boston. It was a home away from home, a small business stitched into the fabric of his everyday life.

“They knew who you were and what you needed,” said Celano, 80.

But the pharmacy landscape today is far different than the one he remembers. Over the past half-century, a flood of chain pharmacies opened across the country, acquiring independent stores, like the ones Celano recalls fondly, or driving them to close.

In 1984, eight decades after its founding in Chicago, Walgreens opened its 1,000th store. By 2009, it operated seven times that many. Now chains control two-thirds of the US market.

The “little guys” who survived proved nimble by ramping up delivery to neighbors and served niches of the population — immigrants, seniors, people with limited English — who preferred familiar hands to touch their prescriptions, said Todd Brown, executive director of the Massachusetts Independent Pharmacists Association, or MIPA.

Chains and smaller operators have since largely made their peace and are banding together against a bigger, common threat: pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs.

First created by pharmacists in the 1960s to process a growing volume of prescription drug claims, PBMs function as the contact point between payers, drug manufacturers, and pharmacies. Just three companies — Caremark, Optum Rx, and Express Scripts — control about 80 percent of the PBM market, estimated to be worth $500 billion a year.

Critics say these companies drive such a hard bargain on drug prices that pharmacies routinely lose money selling prescriptions because the insurance reimbursements determined by PBMs do not cover the medication and administrative costs the drugstores incur. A study from MIPA found that in 2019, 26 percent of claims paid by PBMs to independent pharmacies in the state were “underwater” in this way, up from 8 percent in 2016. On average, PBMs received $4.06 more per claim than they paid out.

CVS, the pharmacy behemoth based in Woonsocket, R.I., is especially entangled with the plight of PBMs, because it owns the largest PBM in the nation: Caremark.

Then-CVS chief executive Tom Ryan called his company’s $21 billion acquisition of Caremark in 2006 a “game changer.” Never before had a retail pharmacy chain owned a PBM, and executives hoped Caremark would steer customers toward CVS stores and boost profits.

But Caremark eventually proved almost too good at its job. Over the ensuing years, the PBM generated massive profits by lowering reimbursement rates, not just at competing corporate and independent pharmacies, but at CVS, too. Executives today admit CVS stores can no longer operate profitably on the rates set by its sister business unit.

CVS Health CEO Karen S. Lynch told investors in December that “the change in the reimbursement levels for the services that we provide do not align with the underlying cost of this business.”

All the while, CVS’s health services unit, which includes Caremark, has become its top performing business. In 2019, it generated $5.1 billion, a third of CVS’s total adjusted operating income. By 2023, that number jumped to $7.3 billion, or 41 percent of overall profits, according to a Globe analysis of its financial statements.

A spokesperson said that reimbursement rates are “not a factor” in deciding about CVS store closures and that they instead consider “local market dynamics, changing customer shopping habits, population shifts, and a community’s store density.”

The company plans to roll out major changes next year in the way its retail stores negotiate contracts with Caremark in the hope of funneling more reimbursement dollars to its retail arm, so stores can eliminate staffing shortages among pharmacists and improve customer service.

In a statement, Walgreens, too, said its closures are a result of the “cost of operating, low prescription volume and low reimbursement rates.” Rite Aid did not respond to detailed questions about its closures.

While reimbursement rates are a problem for the hulking chains, they can spell doom for smaller independent pharmacies with less bargaining power.

PBMs steer profitable orders to larger pharmacies that they own or are affiliated with, a practice that reduced the margins at Massachusetts’ independent drugstores by an additional 20 percent in recent years.

“When it comes down to it, the math is simply not working,” said Dima Qato, an associate professor at the University of Southern California who studies pharmacy access and health equity.

Five independent pharmacists in Boston agreed, saying that insurance companies offer them dismal reimbursement rates for medications, and the challenge is most acute in low-income enclaves of the Commonwealth, where many independent pharmacies operate.

Public insurance, such as Medicare and Medicaid, often pays less for prescription drugs than private plans, and patients who rely on public insurance are more concentrated in poorer neighborhoods.

In the meantime, many pharmacies are left with a difficult choice: Turn away customers who lack adequate insurance, or eat the losses and try to make the money back in other ways. Some lease medical equipment or sell items like house slippers. Others peddle lottery tickets or take in clothes for tailoring, just to keep the doors open.

Tuan Tran, for example, sells rice noodles at Kimmy Pharmacy. He opened the Fields Corner outpost after migrating from Vietnam three decades ago and built a dependable business — decorated with festival flyers, a small business certificate of recognition, and a plaque engraved with the publication date of the first Boston Globe feature on his store, May 29, 2000.

It is not enough. Profits are not what they once were, Tran said. Prescriptions make up an ever-smaller share of his revenue. He stays open for the good of his customers, a small base of older immigrants.

“If I do not help people, if I do not eat the cost,” Tran asked, “who will?”

For those lacking access to prescriptions, a bitter pill to swallow

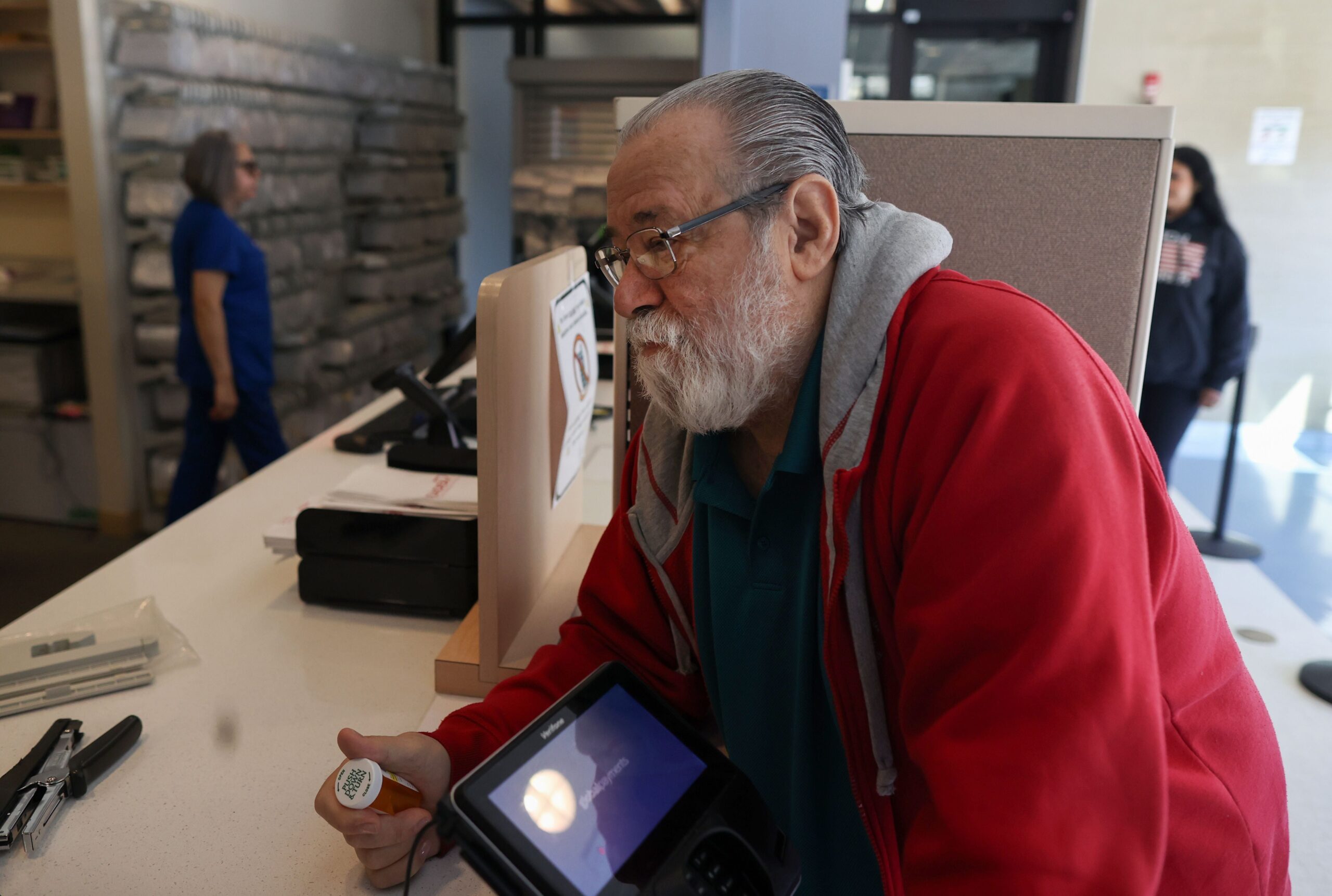

Mail-order prescriptions are often touted as the simple solution to the spread of pharmacy deserts. But consider the pitfalls: Delivery services can be unreliable. Packages may be stolen, lost, or misaddressed. Some elders lack reliable internet access, advocates note, and pharmacy websites can be confusing. Others simply want a professional they can ask about the pills they swallow.

For years, Stephanie Thomas would pick up friends’ medications and explain what to take and when based on the pharmacists’ instructions.

“I did it, happily,” she recalled, reclined in an armchair in her Roxbury home. “People found their way to me.”

Then Thomas herself fell ill with heart trouble, an aching right foot, and bouts of anxiety and depression. Her own medications are now delivered from Kornfield Pharmacy, a drugstore that has served Nubian Square for several decades. Thomas has little faith in FedEx or the flat silver slots where mail is delivered in her apartment building’s vestibule. She feels confident her medicine will arrive on time only because Kornfield owner Esther Egesionu comes and drops it directly in her hand.

“I trust Esther,” Thomas said.

Others lean in the same way on Victoria Okeke. She owns Blue Hill Pharmacy in Grove Hall and spends most of her time making house calls, delivering medication one customer at a time to the elderly and immobile across neighborhoods and suburbs south of Boston.

Each day, Okeke maps out a driving route full of shortcuts and side streets. Just after 4 p.m. on a March Tuesday, she tucked two blister packs into a bag and set off for two deliveries in Mattapan and the South End. Sometimes, customers call, frantic, needing an emergency delivery that alters her meticulous route.

“I don’t care how many patients I have, even if they’re 20, 40, 50 of them. It’s OK,” Okeke said. “I’ll take care of 50 people if 50 people are living healthier.”

“Once a big chain like Walgreens is gone, there’s a void in that community, a big void. And with that void, the question is: How do we fill that gap?” she said. “I don’t want to be the only person to fill the gap of Walgreens.”

But what about those with no other options?

People like Dorchester resident Linda Sokolowski, for example. At 62, she cannot drive or even stand for long periods without her lower back or legs flaring in pain. Every day, she takes a patchwork of pills to manage her liver transplant, fibromyalgia, osteoporosis, lingering long-COVID symptoms, and two knee replacements that left her without a right kneecap.

Walgreens used to leave a monthly package of medications on her front door, until they stopped accepting her MassHealth WellSense insurance plan last year. She switched to CVS, but they, too, refused doorstep delivery, because of the limitations of her insurance.

A healthy person could walk to the CVS on Morrissey Boulevard in 25 minutes from her apartment in the St. Mark’s section of Dorchester. But it would take Sokolowski an hour, with stops to rest on street curbs, she said. Her brother-in-law drops by the CVS for her around three times a week. Without him, she would be at high risk for rejecting her liver, forming blood clots, and losing her already hampered mobility. And she would not be able to care for her 11-year-old granddaughter, Savannah, who lives with her.

Sokolowski thinks often of the thousands of Bostonians in similarly tenuous situations, shut out from access to medication by either geography or circumstance. No pharmacy for miles, no alternative options.

“A prescription,” Sokolowski said, “is no good if you can’t reach it.”

How we reported this story

The Globe used retail drugstore location data from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health and demographic data from the US Census Bureau at the block group level for this analysis. Block groups are statistical divisions of about 600 to 3,000 people.

To identify pharmacy deserts in Boston, we created a radius around each open drugstore — a half mile for block groups with below-average access to cars, and one mile for those with above-average access. We then calculated how much of each block group fell within that radius. The block groups where the overlap was 50 percent or less are considered pharmacy deserts.

Olivia Yarvis of the Globe staff contributed to this report.

Extra News Alerts

Get breaking updates as they happen.