Evidence of construction activities

Excavations in Pompeii’s Regio IX Insula 10 have provided valuable insights into the nature of ancient construction practices, and the scale and organization of the renovation efforts following the catastrophic earthquake of 62 CE. This series of residential construction projects, designed to stabilize and improve various structures in the vicinity, included raw material production areas and provided strong evidence for systematic resource management and material reuse.

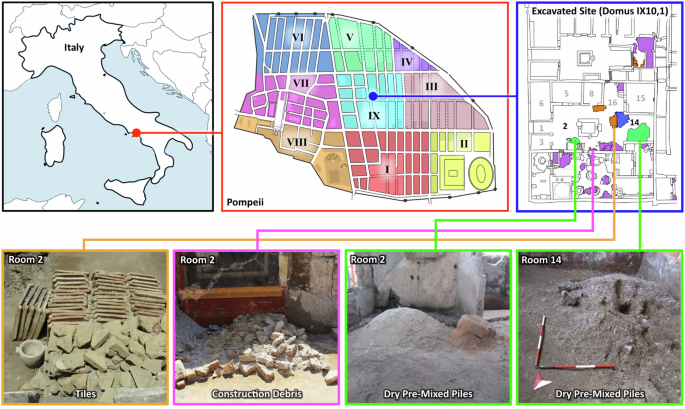

The excavated rooms revealed numerous stacks of recycled building materials, including lava stones, limestone, tile fragments, and pieces of common ceramics and amphorae, all carefully set aside for reuse in ongoing masonry work (see Fig. 1: tiles in orange, residual material in purple, inert material piles in green, and tuff block stacks in blue). Additional building materials were identified in rooms 7 and 16, the latter located at the base of the stairs to the upper floor. The collection and arrangement of these archeological finds support the conclusion that this area served as an active construction site, where raw materials and tools were stored and systematically used (see Supplemental Materials for further details). Construction marks on walls, including sequences of numerals and symbols (Supplementary Fig. 2), may have served as reference points for work schedules, material quantities, or budgeting, providing rare evidence of project management practices in the ancient Roman building industry. In Room 5, several key artifacts were also uncovered, including a lead weight and iron tools such as an ax (Supplementary Fig. 3). The lead weight was medium-sized and conical, retaining an iron handle for suspension, a design consistent with counterweights for balance scales at the time. This discovery suggests its possible use in the precise measuring of material ratios, which would be required to create consistent cement and mortar formulations during the construction process. Room 13 contained additional work tools, both on a masonry bench along the northern wall and on the floor. Smaller items were also found along with nails and mineralized wood fragments, supporting that the objects were all likely stored in a wooden box. Notably, these objects included two plumb bobs, one bronze and the other iron. The bronze plumb bob exhibited concentric ring decorations and a knob with a hole for a string, suggesting its use in marking verticals, an important task in the erection of walls. The iron plumb bob included a small goat horn that was likely used as a spool for suspending the weight. These tools are indicative of precise construction practices likely used by skilled laborers, essential for the correct alignment of architectural elements. Among the tools was a small chisel with two cutting edges perpendicular to each other, used for cutting stones like tuff, pointing to active stone working at the site.

Aside from tools, other significant evidence of construction activities could be inferred from the variety of piles and stacks of materials. Tile fragments were concentrated in room 28. In the northeast corner, a stack of fragmented tiles was laid atop other stones, suggesting that these tiles were being sorted and prepared for reuse (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). These tiles were likely used in the restoration of the roofing or flooring, and the careful stacking and organization of the tiles suggest workers were systematically organizing these materials. Another significant find was the presence of Neapolitan Yellow tuff in various locations throughout Domus 1, particularly in room 2 (the atrium) and near room 14 (the tablinum). The tuff was specifically imported for use in critical concrete structural elements, such as doorposts, corners, and arches. The strategic placement of this tuff in the house suggests that it was likely earmarked for specific structural repairs or enhancements, particularly in load-bearing areas that required the strength and durability of this imported stone. In room 2, a stacked pile of parallelepiped tuff blocks and orderly rows of roof tiles (imbrex) were also discovered (Fig.1). Next to the tuff blocks, was a work area containing small-sized chips of tuff stone, the result from rough shaping the square blocks with an ax (dolabra) to become facing stones (caementa) for the room’s wall repairs.

In room 15, three orderly rows of flat roofing tiles (tegula), along with three piles of concave roof tiles (imbrex), and a corner gutter roofing tile (collicia), were also found. These tiles showed clear signs of wear, suggesting that they had been dismantled from existing structures. The careful storage of these tiles suggests that they were intended for reuse, possibly in the reconstruction of the house’s roof.

In room 2 (Fig. 1), a pile of pre-mixed materials (consisting of lime and fine and coarse aggregates) together with a pile of cocciopesto that showed the imprint of a basket, was found. Most notably, in room 14, there was a large pile of pre-mixed materials with an imprint from a shovel-like tool present (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 4). This pile contained large (several millimeters in size) low-density granules of quicklime, which were dry-mixed with pozzolan and stored for immediate use in the ongoing masonry work. Near this pile, in room 7, the mortar on the wall showed signs of being repaired and reapplied, and a wall between rooms 7 and 13 appeared to be in the process of being constructed (see Supplemental Supplementary Fig. 1). In corridor 10 and courtyard 12, several lime-containing broken amphorae were also found (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Wall construction—a multi-scale characterization analysis

Domus (residential dwelling) 1, in Insula (block) 10 of Regio (region) IX of Pompeii Archeological Park was excavated in January 2023 (Fig. 1). For this study, samples from this location were collected from a pre-mixed (PM) dry material pile, a newly constructed wall that was being built in 79 CE (W1), a completed buttress wall nearby (W2), a pre-existing structural wall (W3), and mortar repairs in an existing wall (MR). Samples were also collected from additional amphorae and material piles located throughout the interior of the domus (see Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1).

To determine the chemical and crystallographic composition of both the pre-mixed material pile (PM) and the walls (MR, W1, W2, and W3), several characterization tools were employed. FTIR-ATR spectra acquired from all of the samples were highly similar and consisted of calcium carbonate and pozzolana, demonstrating uniformity in their basic chemical composition (Supplementary Fig. 6). X-ray diffraction (XRD) conducted on the samples further identified the primary crystalline phase as calcite, along with a variety of alumino-silicate peaks that align with minerals such as leucite and biotite, consistent with minerals found in other Pompeian mortars from early Imperial building phases (Supplementary Fig. 7)33. The similarity in all peak positions and relative peak intensities, and the degree of crystallinity across all samples, further demonstrated their compositional consistency.

Under plane-polarized light (PPL) and cross-polarized light (CPL) analysis, all of the samples (PM, MR, W1, W2, and W3) showed strong petrographic similarities (Supplementary Fig. 8). All samples contained primarily rounded, aphyric to poorly porphyritic volcanic aggregate composed of pumices and lithics. When combined with the findings from Raman (see below) and XRD, these results confirmed the presence of leucite, sanidine, and biotite in the lithics. The binders were predominantly microsparitic, with W1 showing some heterogeneity due to unmixed binder zones and calcite inclusions, and PM and MR exhibited homogeneous textures. Reaction rims were prominent between the unaltered volcanic glasses and binder in all samples, which are indicative of active pozzolanic/post-pozzolanic reactions. Lime clasts ranging from 0.2 to over 1 mm in size were also common, and exhibited porosity, birefringence, and shrinkage fractures (Supplementary Fig. 9).

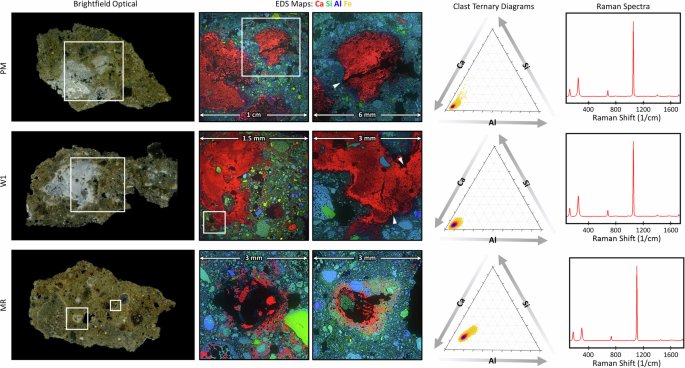

SEM-EDS analysis on sample cross sections revealed porous lime clasts, with Si and Al relatively well distributed throughout the adjacent matrix. Ternary diagrams of Ca, Al, and Si ratios were generated42 for all samples (Fig. 2), highlighting a distinct difference between W2 and the other samples, with PM and W1 displaying highly similar distributions and volume fractions of Ca, Al, and Si. The Ca/Si fractions within the PM and W1 matrix were slightly lower than in MR and significantly lower than in W2. The auto-correlation functions applied to the EDS maps further support this differentiation, with volume fractions for Ca, Al, and Si closely matching between PM and W1, while W2 showed notable divergence (see Supplementary Text). Additionally, the shapes of the autocorrelation and two-point cluster functions for PM, MR, and W1 were similar to each other, but distinct from W2, and markedly different from those observed in an ordinary Portland cement reference mortar (see Supplementary Text). The strong similarity between PM and W1 suggests a common origin, supporting the hypothesis that the dry, pre-mixed materials served as a source material for both mortar repairs and the construction of new Roman concrete wall sections.

The leftmost column displays the locations of concrete samples from Roman architectural components (with points of sample collection denoted by white asterisks). The second column displays brightfield optical micrographs of cross sections of the pozzolan/lime pre-mixed dry materials and mortars, highlighting large lime clasts (denoted by red asterisks) in the PM and W1 samples, alongside a relatively uniform pozzolan-based matrix throughout all samples. The third and fourth columns present SEM backscattered electron micrographs and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) maps, highlighting the morphology and chemical composition of the pozzolan matrix. The ternary phase diagrams in the fifth column illustrate the compositional differences within the Ca-Al-Si system. The wall sample W2 clearly contrasts with other pozzolanic mortars and pre-mixed dry materials, all of which exhibit highly similar ternary diagrams. These results are corroborated by bulk composition quantification (atomic % of Na, Mg, Al, Si, K, Ca, and Fe) for each sample (column 6), showing a larger Ca concentration in W2 compared to other samples (average values plotted from n = 3, and error bars correspond to ± one standard deviation).

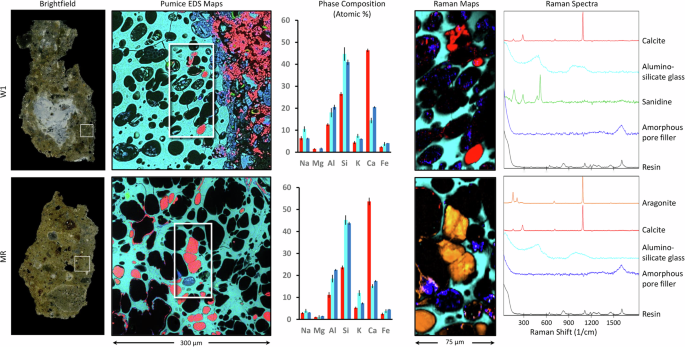

SEM/EDS imaging and ternary diagram analyses of the lime clasts in samples PM and W1 (Fig. 3) showed that they are predominantly calcium-rich, and their corresponding Raman spectra (Fig. 3) revealed that they are primarily composed of calcite. These clasts are all characterized by distinctive cracking and a high degree of internal porosity, with some displaying signs of hollowing or partial dissolution (Fig. 3 sample MR). Elemental mapping also revealed increased concentrations of Al and Si, both around aggregates and along the rims of the lime clasts (Fig. 3, samples W1 and MR).

Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) maps show the elemental distributions of Ca, Si, and Al, with lime clasts appearing prominently in red, demonstrating their high calcium content. The top two rows (PM and W1) reveal lime clasts with similar characteristics, notably displaying distinctive cracking patterns (right EDS maps; cracks denoted with white arrowheads), which are indicative of the use of quicklime and hot mixing techniques. In contrast, the third row (MR) shows lime clasts undergoing evident dissolution, suggesting ongoing reactivity within the matrix that may contribute to long-term structural resilience through the progressive transformation of lime phases. The two rightmost columns provide ternary phase diagrams and Raman spectra of the clasts, showing their mineralogical composition and chemical environment within the matrix.

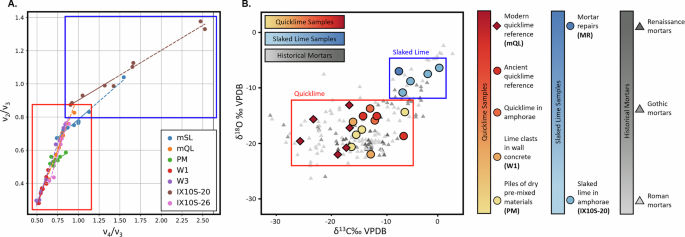

The lime clast crystallization kinetics were further investigated using transmission FTIR and mass spectrometry (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 6). Using the same metrics as in Chu et al.43, the v2 and v4 vibrational modes in the samples, located at approximately 870 cm−1 and 713 cm−1, respectively, were analyzed after different durations of mechanical grinding in order to identify the extent of crystallinity of the carbonate phases. The v2 and v4 normalized values were plotted (see Fig. 4 (left)) for both the modern quicklime (mQL) and slaked lime (mSL) references, and the ancient (PM, W1, W3, IX10S-20, and IX10S-26) samples. A notable difference in the grinding curve slope was exhibited between the mQL and mSL samples, which was subsequently used as a reference to group the archeological samples into quicklime (red box) or slaked lime (blue box) precursors (Fig. 4 (left)). Since the ν2 and ν4 vibrational modes are most sensitive to in- and out-of-plane lattice distortions, the shallower slope in the mSL and IX10S-20 samples suggests that Ca(OH)2 underwent less extensive reconfiguration of its crystal structure over time (likely through hydration and carbonation), which would lead to the formation of more ordered phases which can be disrupted by an applied strain. In contrast, the steeper slope in the mQL sample implies a lower starting degree of order, and a more structurally uniform, but disordered material, where ν4 changes minimally with progressive grinding. The alignment of the PM, W1, and W3 samples with the mQL reference line strongly supports the presence of carbonated quicklime as a raw material in these samples, which is suggestive of a rapid crystallization process. Across all samples, the unnormalized ν2/ν4 peak ratios were slightly lower than those reported in the literature for other archeological mortars, which could in part be explained by the presence of amorphous calcium carbonate in the lime, determined through TGA of the mQL and mSL reference samples (Supplementary Fig. 10).

A Normalized transmission FTIR vibrational mode intensity ratios across samples from this work, subjected to progressively longer grinding times. The distinct slopes of the modern reference slaked lime and quicklime (mSL and mQL) grinding curves were compared to the lime in the ancient samples. The lowest ν2/ν4 ratios were observed for samples identified as ancient quicklime (grouped in red the red box), suggesting a lack of long-range initial order. The grouping in the blue box shows samples with higher ν2/ν4 ratios, suggesting the presence of slaked lime. B δ13C and δ18O isotopic compositions of carbonate samples from Pompeii (circles), modern samples (diamonds), and ancient Roman, Gothic, and Renaissance mortars and plasters from Kosednar-Legenstein et al. (gray triangles). Samples with quicklime clasts from Pompeii (red and orange circles) are lighter in both δ13C and δ18O (grouped in the red box) than the Pompeii-collected slaked lime samples (blue circles), and approach values from modern quicklime (mQL, dark red).

Stable isotope mass spectrometry provides an additional method for investigating the environmental and chemical conditions that influenced the formation and alteration of ancient carbonate materials. This technique measures the ratios of the rare heavier isotopes to common lighter isotopes of carbon (13C/12C) and oxygen (18O/16O). Mass spectrometry can distinguish between different reaction environments because isotopic signatures vary depending on carbonation conditions, with shifts caused by differences in water availability and atmospheric CO2 uptake during carbonation processes. For example, lime carbonation proceeding slowly in water-rich environments at near equilibrium conditions has a different signature than carbonation resulting from the rapid absorption of atmospheric CO2 through a thin film of water, which can drive kinetic isotope fractionation. Equilibrium precipitation would have values near the origin, depending on local water composition, whereas the combined kinetic isotope effects from hydration of atmospheric CO2, which follows a slope of ~0.6–0.7 in a δ13C vs. δ18O plot, and hydroxylation of atmospheric CO2, which follows a slope of ~1, have a maximum negative δ13C shift of 26–31‰ and δ18O of 27–30‰. The relative importance of each kinetic process is pH dependent; in hot mixing, which occurs at high pH in water-limited conditions, hydroxylation is likely to be a dominant process44 providing an independent method to differentiate between carbonation conditions (Fig. 4B).

Previous measurements of δ13C and δ18O by Kosednar-Legenstein et al.45 of ancient Roman, Gothic, and Renaissance mortars and plasters show a broad scattering with a positive correlation between δ13C and δ18O, with a slope of ~0.7 (Fig. 4B, gray symbols). The samples from the Pompeii archeological site overlap with these previously published values, but largely fall into two distinct populations (Fig. 4B). These populations correspond to materials identified as quicklime (red box) and slaked lime (blue box). mQL (the modern quicklime reference) is one end-member with the lightest δ13C and δ18O values. Within the ancient quicklime population, the light δ13C and δ18O values are consistent with large kinetic isotope effects from atmospheric CO2 hydration and hydroxylation in a water-limited environment (Fig. 4B, red box). This pattern is consistent with hot mixing involving direct quicklime addition and in situ carbonation. Both the δ13C and δ18O values are heavier in the slaked lime samples from Pompeii, with IX10S-20 representing a second end-member (Fig. 4B, blue circles). These values suggest precipitation closer to isotopic equilibrium, with the δ13C reflecting dissolved inorganic carbon and δ18O reflecting precipitation from local water at ambient conditions. Importantly, all samples in this study were collected prior to modern restoration efforts, so the isotopic variations reflect the original construction practices rather than post-depositional interventions.

Post-pozzolanic aggregate/matrix interfacial remodeling

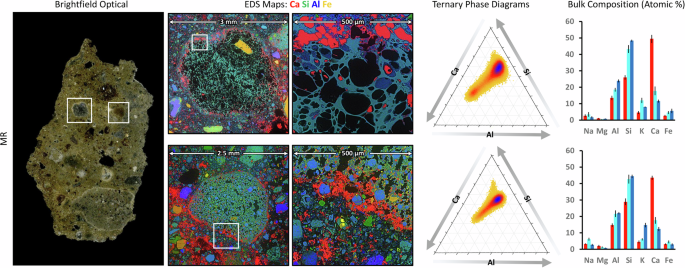

Across PM, MR, W1, W2, and W3, reaction rims were observed; Fig. 5 illustrates the reaction rims present around pumice particles in the mortar, offering details about the long-term chemical processes within the volcanic aggregate-matrix interfacial zones. The brightfield optical micrograph on the left indicates regions of interest within pumice particles situated in the cementitious matrix. These regions (highlighted by white boxes) represent areas where extended remodeling reactions are distinctly observable as reaction rims at the pumice-matrix interface. The EDS maps in the second and third columns show the elemental distributions within the interfacial zones, where two distinct features are observed: (i) calcium-rich mineralization (red) at the border and in the vesicles of the vitreous pumice aggregates, and (ii) Si and Al-rich mineralization (blue and green) in the vesicles of the pumice. The presence of these pumice fragments within these samples thus provides a unique opportunity to unequivocally identify these sites of chemical transformation, since new mineral formation can be clearly visualized within the native internal voids of the pumice fragments (Fig. 5).

EDS elemental maps (second column) of two entire volcanic aggregates reveal elemental distributions, emphasizing the complex interplay between Ca, Si, and Al across the pumice/cement boundary, and a clearly visible enrichment in calcium at the interface. Ternary phase diagrams of the interfaces (fourth column) demonstrate compositional trends reflecting interfacial remodeling, with two main regions in the diagram: one (upper) more intense, containing less calcium and more Si and Al; and one (lower) more enriched in calcium. The compositions of red, blue, and cyan regions are plotted using compositional histograms (fourth column), showing the atomic percentages of Na, Mg, Al, Si, K, Ca, and Fe. These results show localized chemical variability of mineral remodeling, implying two main phases at the interface: (i) a blue phase rich in Si, Al, and some Ca, and (ii) a red phase rich in calcium with some amount of Si and Al (average values plotted from n = 3, and error bars correspond to ± one standard deviation).

The ternary phase diagrams and bar graphs reveal the compositional relationships of Ca, Si, and Al within the reaction rims (Fig. 5, right). Red regions denote the presence of Ca-rich phases with the elemental composition resembling Ca:Si:Al ratios of ca. 5:3:2, whereas the blue regions denote the presence of aluminosilicate phases with Ca:Si:Al ratios of ca. 1.5:6:2.5, and similar to the unaltered pumiceous glass. For a more comprehensive analysis of the various phases and their compositional differences, see Supplementary Fig. 11.

While these EDS mapping data can provide critical information regarding the elemental distributions within the different samples, they cannot identify the specific mineral polymorphs present. Raman confocal imaging enables the spatially resolved identification of mineral phases within pore spaces, revealing post-depositional transformations in the pumice glass matrix. This technique can be employed to help trace mineral evolution in the vesicles, offering a clearer understanding of in situ chemical and environmental changes (Fig. 6). The Raman spectra demonstrate calcite (the most stable polymorph of CaCO3) as the dominant mineral phase, which exhibits characteristic Raman peaks including the symmetric stretching mode of carbonate groups (~1085 cm−1) and lattice vibrational modes at ~280 cm−1 and ~155 cm−1. In addition to calcite, the Raman data also revealed the presence of aragonite (a less stable polymorph of CaCO3), identified through its distinct peaks, including the symmetric carbonate stretch at ~1085 cm−1 (shared with calcite), ν4 doublet at 701 and 706 cm−1, and characteristic lattice modes at ~208 cm−1 and ~152 cm−1. The simultaneous presence of calcite and aragonite in the vesicles of the pumice glass suggests that post-pozzolanic carbonation processes have been influenced by localized variations in chemical conditions, such as Mg/Ca ratio, temperature, and kinetics during the carbonation stage22. The dissolution and recrystallization of carbonates into stable calcite and aragonite forms a self-repairing layer at the interface (Fig. 6, Raman maps). Interestingly, the Raman data do not show significant peaks associated with aluminosilicate frameworks, demonstrating that previously literature-reported46 crystalline zeolites, such as chabazite (K2CaAl4Si8O24·12H2O), are absent or poorly represented in the vesicles of the pumice glass. However, the detection of significant levels of Si and Al in the SEM-EDS data suggests the presence of an amorphous or poorly crystalline aluminosilicate matrix (most likely C-A-S-H), potentially originating from residual pozzolanic reaction products or volcanic glass. The precipitation of calcite, aragonite, and C-A-S-H not only stabilizes the concrete but also reduces porosity by filling micro-cracks and voids, hence improving resistance to water intrusion.

Brightfield optical micrographs from the sample cross-section (left) show macroscopic features, including large lime clasts and a pozzolanic matrix (W1). Pumice EDS maps (second column) highlight elemental distributions at the pumice/cement matrix interface. The phase composition histograms (third column) plot atomic percentages of Na, Mg, Al, Si, K, Ca, and Fe in the red, blue, and cyan regions (average values plotted from n = 3, and error bars correspond to ± one standard deviation). Raman maps (fourth column) reveal chemical variations in the inclusions, with characteristic spectra (right) identifying phases such as calcite, alumino-silicate glass, sandine, amorphous pore fillers (in W1), and aragonite (in MR).