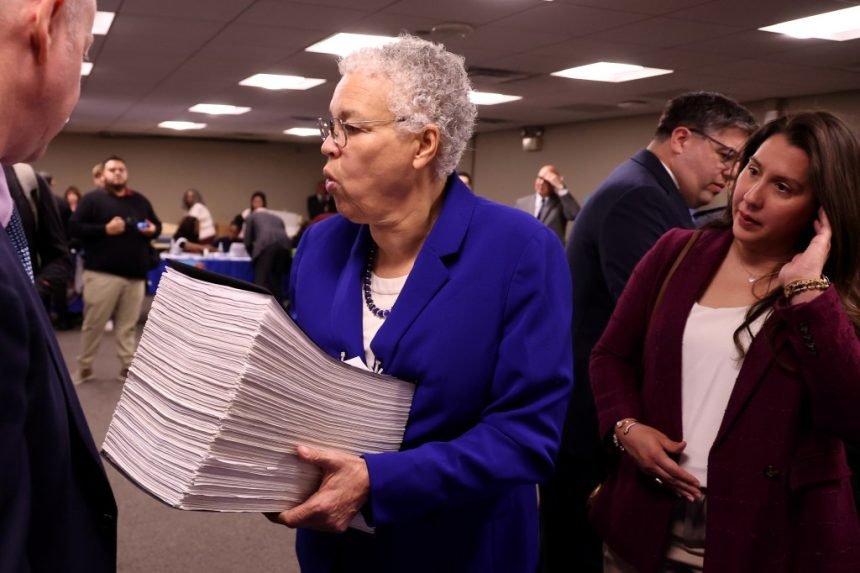

Cook County’s system to give property tax breaks to businesses is set to expire in two years, and Board President Toni Preckwinkle is looking to revamp the program that has already shifted billions of dollars in tax levies into the wallets of homeowners and other property owners.

While most Cook County residents are likely scarcely aware of the tax incentive program, its impact is far-reaching.

In 2022 alone, more than 90 municipalities across the county granted the breaks to qualifying businesses, taking $7.58 billion of those properties’ fair market value off the tax rolls, according to an analysis released by Preckwinkle’s office Friday.

That pushed $343 million onto property tax bills for other homeowners and businesses that year. But local officials generally consider incentives to be worth it to drum up jobs, broaden the county’s tax base and prevent industrial businesses from decamping to lower-tax competitors in Will County or Indiana.

The new analysis, though, found that there is little data to track whether the incentives are actually accomplishing those goals. One certain conclusion is that a 2009 break developed to help ailing south suburban communities has lost its edge.

And furthermore, the study found, the system is “difficult to navigate, opaque to outsiders, and fractured across different public offices,” making applicants reliant on pricey attorneys with know-how.

Economic development policy experts tend to agree that incentives shouldn’t be given to businesses that don’t need them, but that need is difficult to prove without examining a company’s books.

Doling out breaks to businesses that don’t need it can force governments to forgo property tax money they could otherwise use to offer better services or infrastructure. It can also fuel a “race to the bottom” where communities offer a pile of incentives to poach business from their neighbors.

The study is part of Preckwinkle’s Property Tax Reform Group and landed at a time when taxpayers are in a fighting mood about their bills. It was commissioned to give county leaders a road map to make the system more fair and effective before the clock runs out on the ordinances regulating the county’s most common incentives.

The Government Finance Research Center at the University of Illinois Chicago and the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning have been studying the issue since 2024 and helped author the report, which recommended 30 fixes for the most common industrial breaks.

The incentives can drastically reduce a business’ property tax bill for over a decade, by dropping the amount of property value on which their tax assessment is based from 25% of the total to 10% for 10 years, then 15% for one year and 20% for a final year in the 12-year deal.

Take an industrial property in Hazel Crest worth $1 million: Normally, when its tax bill is calculated, it would be assessed at 25% of its value, or $250,000. With a “6b” incentive, it’s assessed at 10%, or $100,000. For the 2022 tax year, that owner’s 2022 bill would be about $77,000 instead of $192,000 thanks to the break.

Incentives are available to a dizzying array of properties. Newly-built, redeveloped or rehabilitated industrial properties; new commercial properties; grocery stores in food deserts and properties developed on former polluted areas known as brownfields can each qualify. The county also offers a three-year break for new or rehabbed commercial properties, and the dedicated 10-year Class 8 break is granted in certain communities “in need of revitalization” — Bloom, Bremen, Calumet, Rich, and Thornton townships.

The use of incentives is especially prevalent in the south and west suburbs and near Chicago’s two airports.

But for the most part, the county isn’t particularly selective about who gets the deals, the report found. Any business that fits the qualifications and makes it through the gantlet of government approvals is considered entitled to a break “by-right,” and its impact is ultimately not studied.

“The county has an incomplete and unreliable record of past applications (especially for unfinished or unsuccessful projects), and the limited information that is available cannot be joined with parcel-level data on properties’ characteristics and valuations,” the report notes.

During the pandemic, the county “also waived the requirement for recipients to submit triennial affidavits about the use, ownership, and occupancy of properties with an incentive.” Both prevented the study’s authors from grading the breaks’ effect on the tax base, job creation or other economic development metrics.

The county should change the application process to not only gather more of that data for municipal and county leaders to analyze, but also to simplify or centralize it for businesses applicants, the report recommends.

Right now, getting an incentive approved includes dealing with as many as five public offices, six votes by four public bodies, and thousands of dollars in fees that take up to three years to complete. Communication between the county’s Bureau of Economic Development and individual municipalities varies, which has fueled some mistrust of the program generally.

The effect of the breaks most closely guarded by local politicos, those in the Class 8 incentive, has also eroded because other incentives have changed to match its advantages. Those changes basically gave applicants the same benefit to locate elsewhere in the county, instead of what the break intended: to get businesses to locate or stay in disinvested suburban communities.

In suburban communities near lower-tax Indiana or Will County, municipal leaders anecdotally consider incentives a lifeline to hold on to businesses or attract any at all. Incentives are used extensively in communities such as Ford Heights, Phoenix, Matteson, Northlake, Bedford Park and Markham, the study found. But it’s hard to know whether businesses would have located in those communities with or without the incentive absent more data.

Industrial tenants’ exit en masse would significantly hike those communities’ already-high tax rates, the report found. But if they stayed after an incentive lapsed, it could dramatically reduce the area’s tax rate. Officials could grant more goodies to Class 8 recipients to induce more businesses to take them, or reduce the length or value of other incentives used around the county.

In general, the report recommended the county consider negotiated agreements that give more flexibility on the terms for incentives such as changing the timeline, the ramp down on the assessment percentage or the discount amount. The county could also consider “pay-for-performance” standards so the breaks only happen after they reach benchmarks.

Business incentives help determine hundreds of millions in shifted property tax burdens annually, but that’s far less than the billions that move around because of homeowner exemptions.

But they are also one of the few property tax reforms the county can tackle on its own without say-so from Springfield. Preckwinkle’s team hopes some targeted changes to incentives aimed at ailing suburban municipalities, paired with a less blanket approach countywide, better administration and a faster application process can deliver more equitable economic development. In the long run they hope to reduce tax rates and deliver other collateral benefits such as more jobs and sales tax revenue.

“We look forward to reviewing the study’s recommendations and working with the Board of Commissioners on next steps,” Preckwinkle said in a release.