It’s a fun time to be a fan of the Boston Celtics. It is also a fraught time, given how polarizing the franchise—and the city—can be to everyone who doesn’t live there. I get it: No one wants to hear from us. New England sports teams have won entirely too much this century (sorry). Our fans can act like entitled dickheads (guilty).

Though I haven’t lived in New England for 30 years, I still feel tribally connected to its teams. That’s how it tends to go for those of us who marinated in the Boston sports experience as kids. And so here we are again. The Celtics are playing for their record-breaking 18th championship against the Dallas Mavericks in the NBA finals. They lead the series 3–0, with Game 4 set for Friday in Dallas. The Celtics are poised to sweep. But if the Mavericks can force a Game 5 in Boston Monday night, and I can find a ticket without going broke, I’m planning to fly home for the occasion.

I only wish the airport I would land at were called Bill Russell International. It should be.

This has been a hobbyhorse of mine for a while. Boston should rechristen Logan Airport to honor the unparalleled Russell. He was Boston’s greatest sports champion, and as a brave and steadfast civil-rights leader across half a century, an even greater man.

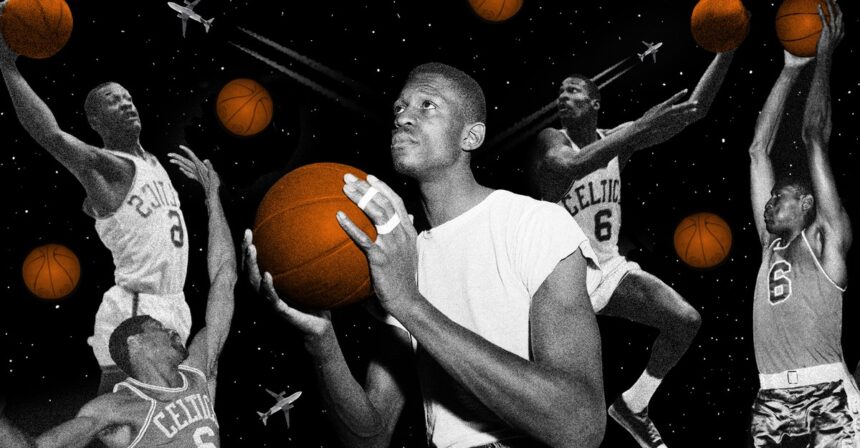

After Russell’s death two summers ago, at 88, the NBA announced that it would retire his No. 6 jersey league-wide, making him the only basketball player ever given that distinction. (Major League Baseball had done the same for Jackie Robinson’s No. 42.) The honor owed less to Russell’s imposing trove of basketball milestones—he led the Celtics to 11 titles from 1956 to 1969, and was the first Black coach in modern professional sports—than to what he endured and fought against during a tragically fractious time in America.

As a vocal Black athlete in the 1960s, Russell traveled a distinctly harsh path through the most resistant sectors of the country. In 1961, before an exhibition game in Lexington, Kentucky, Russell and some of his Black teammates were denied service at a local restaurant—leading them to walk out and boycott the game. Another time, on the same night that the mayor of Marion, Indiana, gave Russell the key to that city, a hotel restaurant refused to serve him. Russell promptly went to the mayor’s house, woke him up, and returned the key.

“Such injustices took a toll,” Russell recalled in a 2020 essay. “I’ll never forget having to drive through the day and night to get some place, ignoring the cries of my still young children, because there was no place to stop to eat or rest, no hotel or restaurant that would accept our Blackness.”

Russell’s outspokenness about civil rights led the FBI to surveil and investigate him, on the erroneous grounds that he had ties to the Black Panthers. He spoke often of the indignities he faced as a matter of routine, ensuring that the racism he encountered became as central to his story as his basketball exploits. This was brutally true in the city he played in; the peak of Russell’s dominance with the Celtics in the 1960s coincided with one of the nadirs of Boston’s racist history. “I played for the Boston Celtics, the institution, and the Boston Celtics, my teammates,” Russell said. “I did not play for the city or for the fans.”

The stories he told were numerous and ghastly. Vandals broke into Russell’s suburban Boston home, spray-painted the N-word on the wall, left feces on his bed. He endured harassment from police, neighbors, and some of the same people who cheered for the Celtics at Boston Garden. After his playing days ended, in 1969, Russell rarely returned to the city. For years, he rebuffed efforts to honor him. When the Celtics retired Russell’s number at Boston Garden in 1972, he insisted that the ceremony take place without fans in the arena.

Eventually, Boston’s leaders came to view reconciliation with Russell as a civic priority, a signal that the city was willing to reckon with its history, mark its progress, and acknowledge—even if it could never erase—the pain it had inflicted on its greatest champion. As the years passed, Russell became a willing partner in rapprochement. In 1999, the Celtics held a special “re-retirement” ceremony for Russell, featuring Larry Bird, Russell’s successor as the team’s resident legend, and Wilt Chamberlain, his former archrival. This time Russell attended—and received an extended ovation, which moved him to tears.

After that, Russell’s returns became more frequent. He became an avid promoter of youth mentoring programs, working closely with Boston’s longtime mayor Tom Menino, whom he would praise as the leader of “a city that embraces the diverse contributions of all its people and neighborhoods.”

In 2013, Boston dedicated a statue of Russell outside City Hall, an honor that followed a prolonged nudging campaign from the highest levels. “I hope that one day in the streets of Boston, children will look up at a statue built not only to Bill Russell the player, but Bill Russell the man,” President Barack Obama had said while giving Russell the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2010.

“Long overdue,” one fan yelled as Russell’s bronze likeness was unveiled at Boston’s City Hall Plaza in 2013.

Overdue—and also not enough. Boston fans boast (insufferably) about their roster of sports heroes. Many of those heroes have statues: A metallic brown likeness of Red Auerbach, Russell’s revered coach, occupies a bench at Faneuil Hall. The Bruins legend Bobby Orr got his statue outside TD Garden in 2010 (three years before Russell’s went up). The New England Patriots plan to erect a 12-foot-high statue of Tom Brady next season outside their stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts. The Red Sox great Ted Williams has not only a statue outside Fenway Park but a highway tunnel under Boston Harbor, connecting the airport to downtown.

It’s about time Boston gave Russell the whole damn airport. His basketball achievements are colossal on their own—Russell is widely considered one of the top five players of all time—but his life in full transcends sports. A proper tribute would be comprehensive, and as big as he was. Statues are nice, but they are static and conventional. “First, they remind me of tombstones,” Russell said at the unveiling of his. “And second, they’re something for pigeons to crap on.”

Naming the airport for Russell would send a powerful message about the region it serves: Boston has come a long way toward racial comity since the benighted 1960s, but its journey is ongoing, and—despite Massachusetts’s liberal bent—has taken longer than it should have.

Airports are works in progress, like cities and people. They represent humanity going places and, ideally, communities striving to catch up. Of course, renaming Boston’s one major airport after 80 years would be complicated, setting off the inevitable hail of “But what about so-and-so or so-and-so?” The city is blessed with a long roster of hometown worthies, many of whom predated the invention of flight. (Paul Revere did his best work on horseback.)

But the case for Russell is too strong. In 2016, Boston magazine published a survey of the “100 Best Bostonians of All Time,” which ranked John and Abigail Adams No. 1 and the writer and poet (and Atlantic founder) Ralph Waldo Emerson No. 2. The highest-ranking athlete on the list was Russell, at No. 11—one behind William Rosenberg, the guy who founded Dunkin’ Donuts. Kind of on the nose, huh?

I mean no disrespect to General Logan. He had a good run. They can rename Terminal C the Logan Terminal or something. Or name a special Dunkin’ after him; there are about a dozen of them at the airport. But Ted Williams has his tunnel, and Red Auerbach has his bench. Let’s give Russell a monument commensurate with his significance to the city, something that is both a celebration of his accomplishments and a goad to the city to meet his towering example. Bill Russell International Airport makes a bold statement, like the man himself always did.