Este artículo también está disponible en español.

Since December 2022, more than 40,000 immigrants have come to Denver, primarily from Central and South America. Many are from Venezuela, where political turmoil and socio-economic instability have caused one of the world’s largest displacement crises. In 2023, more newcomers arrived in Denver per capita than anywhere else in the United States. The influx reached a peak earlier this year, in January, when hundreds arrived in Denver each day, mainly from U.S.-Mexico border states.

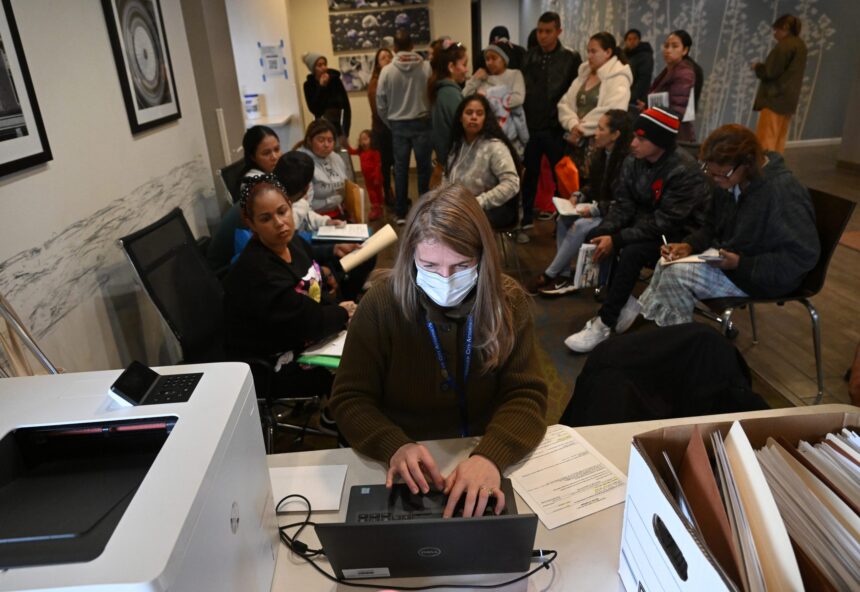

By the end of last year, Denver had converted seven hotels to emergency shelters, on top of a handful of other smaller, congregate shelters. The city also began offering asylum and work-permit application assistance earlier this spring. But once they reach their shelter-stay limits — roughly two weeks for individuals and six weeks for families — hundreds of immigrants began living in encampments. Others have obtained leases from city-run programs but then lost their housing because they couldn’t keep up with rent payments. The city has offered shelter to currently unhoused immigrants, but many are reluctant to re-enter the system, citing the poor conditions inside shelters. City officials have continually asked federal officials for more funding, to no avail.

Officials say that the influx has since slowed; since February 2024, only a few dozen immigrants have arrived each day. On April 10, Denver rolled out the Denver Asylum Seekers Program, an initiative designed to support asylum seekers for up to six months. Activists criticized the new plan, however. The city is limiting shelter stays for new arrivals to 72 hours. Many argue that 72 hours is not enough time to find long-term housing and is more likely worsen the city’s homelessness crisis. But officials say it’s necessary to limit shelter stays, because the influx of newcomers over the past two years has strained the city’s resources.

High Country News spoke to Sarah Plastino, the Newcomer Program director for the city and county of Denver. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

High Country News: Why is Denver moving away from housing people for longer periods of time?

Sarah Plastino: Our system previously was very financially unsustainable. At our height, we were housing over 5,000 people in hotel rooms. That was on track to be over 10% of the city’s budget. Any unbudgeted money we spent had to be cut elsewhere. We needed to get a handle on the scope of our services and intentionally work to integrate the folks who are settling into Denver.

HCN: How does Denver’s new response plan differ from what was in place previously?

SP: The Denver Asylum Seekers Program aims to serve individuals who plan to apply for asylum (but can’t yet obtain a work permit). Those individuals don’t qualify for work authorization until six months after the date they file their asylum application. We’ve designed a program that provides six months of wraparound services, including rental and food assistance, case management, transportation and free legal services to submit asylum and work-permit applications. We want to capitalize on that waiting period and set folks up for success. Admittedly, we are serving a smaller number of people, but we are serving them better.

HCN: Who qualifies for the Denver Asylum Seekers Program, and what support will new immigrants who don’t qualify for it receive?

SP: All of the people who were in our shelter system as of April 10 and who did not enter the U.S. through the CBP One App are eligible. (Editor’s note: The CBP One App is available to migrants coming from Central and Northern Mexico. People can use it to schedule appointments to present themselves for screening at a port of entry along the Southwest U.S. border. However, the CBP One app has been riddled with bugs, and appointments can take months to obtain. The practice has spurred border crossings outside ports of entry and is facing ongoing litigation. Plastino said that the majority of people who come to Denver have not used the CBP One App; instead, they crossed the border outside of an official point of entry and turned themselves into the Border Patrol, where they can be detained or put in the asylum court system.) We initially estimated that about 1,000 would be eligible, but that number turned out to be closer to 800 when the program launched on April 10. However, any newcomer who has arrived in Denver after April 10 will not be offered a spot in the program. We’ll develop a waitlist for other folks, so if people graduate or decide to move on their own, they can plug into the program as spots open.

Our pre-existing system will continue to serve new immigrants and the immigrants who are already here. People ineligible for the Asylum Seekers Program are immediately eligible to apply for a work permit, and we have ongoing clinics for those folks to apply for their work permits for free. Families also have access to up to $4,500 of rental assistance funds through the state. (Plastino notes that there are requirements for new immigrants to receive shelter, mainly an Alien Registration Number [A-Number]. Border Patrol is supposed to give every migrant they process an A-Number when they enter the U.S., but that doesn’t happen in almost 25% of cases. New immigrants that are not processed by the Department of Homeland Security cannot access shelter. The ratio of new immigrants in Denver who do have A-Numbers versus those who don’t is unknown.)

HCN: What happens to new arrivals in Denver now that the new program is in place?

SP: Many people want to reunite with their friends and family, so we pay for their transportation to reunite them with their support network, whether that’s local or somewhere else in the country. At the Denver reception sites, we have navigators who help newcomers make a plan and identify resources. And in the event that folks do remain in Denver, we allow them 24 to 72 hours in shelters to figure out their plans or to accomplish specific things like reuniting with family, getting medical care, or complying with an immigration directive. And beyond that, it’s tough.

HCN: What happens if people can’t find shelter after 24 to 72 hours and end up unhoused?

SP: The city does not continue to provide shelter. And that’s a really difficult aspect of this. Our sheltering policy was causing people to choose to come to Denver, and the city couldn’t indefinitely shelter people in such large numbers. But we’re not the only game in town. There are dozens and dozens of nonprofits that are providing support to newcomers in a variety of ways as well as other folks in Denver in need.

HCN: Do you have any recent data for how many immigrants are unhoused currently?

SP: We don’t have good data on that.

HCN: Have you found that 24 to 72 hours is enough time for people to find shelter?

SP: Actually, yes. Currently we’re receiving about one to two buses a day, around 20 to 30 people. The vast majority of almost everybody that arrives on the bus figures out their situation within the afternoon. Currently, there are only 31 individuals in short-term shelter.

HCN: Are you communicating with officials in other cities in the West to coordinate responses and share information and best practices?

SP: Yes. Mayor (Mike) Johnston is active in the United States Conference of Mayors. (Editor’s note: the Conference of Mayors is a nonpartisan organization of cities with populations of 30,000 or more, where mayors can promote and develop policies and share resources.) We have folks in the mayor’s office who are responsible for coordinating with other municipalities throughout the region. We developed a playbook for local governments who might be interested in learning from our experience, which outlines how to implement programs Denver has implemented. We respond to anybody who asks for help and provide them technical assistance.

HCN: What is your plan in case the federal administration doesn’t change its immigration policies, especially if a large influx of migrants come to Denver?

SP: We have learned that we can’t wait for the federal government to act. So over the course of the next six months, we’re rolling out the new program, refining it, and hoping to make it sustainable long-term. We are prepared in the event that a large number of people start arriving in Denver again. We’re developing new congregate sites so that we have capacity outside of the hotel system.

Natalia Mesa is an editorial intern for High Country News based in Seattle, Washington, covering the Northwest. Email her at natalia.mesa@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.