It was the early 1980s and I’d been Habitat for Humanity’s executive director for a year or so of this nascent New York City project. I was only around 25 at the time.

We laid claim to this building on East 6th Street but didn’t have ownership. The Lower East Side was like the South Bronx at that time—pretty bombed out, with frequent fires destroying buildings. It started to become gentrified, but nothing like it is today.

Habitat International in Georgia was not very well known back then, with only several dozen projects around the world, many of them in Africa and elsewhere in the Americas.

But former president Jimmy Carter, two years out of office, had become interested in Habitat.

One day, I happened to pick up the New York Daily News, which I never read. There was a small article saying Carter would be in New York to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the installation of the Greek Archbishop, a friend of Carter’s, on April 1, 1984.

I sent the clip to Millard Fuller, the founder of Habitat who had recently gotten Carter interested in the organization, thinking it’d be great if the former president could stop by our project while he was in New York, but never believing it would be possible.

Newsweek Illustration/Getty/AP

Millard woke me up at about 7:00 in the morning with a call. He said: “Rob, I got news for you. Jimmy Carter’s coming to your project.”

Well, that got me up. We made plans for Carter to come, and my instructions were to meet him on Sunday morning in the presidential suite of the Waldorf Astoria on Park Avenue.

I had never met anyone of that stature before. I was so nervous waiting outside the suite that it felt like someone had stuck a vacuum cleaner hose into my mouth and sucked out all the moisture. Then he showed up.

One of the first things I noticed was how old he looked compared to when he left office. It happens to everybody; the only president who looked younger at the end of his time in the White House was Ronald Reagan.

I said, “Hello, Mr. President,” thanked him for coming, and then I pulled out these cheesecakes from a famous deli in Brooklyn called Junior’s.

I said: “Mr. President, if you don’t come back to New York for any other reason, you have to come back for Junior’s cheesecakes.”

I pulled out the first one and said: “This one’s for you and…Mrs. President.” I didn’t even know what to call her. And then I said: “And this one’s for Nancy Konigsmark.”

Nancy had been married to Hamilton Jordan, a staffer in the White House, and she was Carter’s appointment secretary. I had been dealing with her about the logistics of the meeting.

Then I said: “And this one’s for these fellows for taking such good care of you,” and pointed to the burly Secret Service agents accompanying him.

Characteristically, Carter was very gracious and said: “Well, thank you, Rob. Thank you very much. That’s very nice.” But I could tell he thought: “Am I in New York City? This is the hokiest thing I’ve ever experienced in my life.”

We got in the car. He’d had a dispute with Ed Koch, the mayor of New York, over Israeli policy. On the way down, he said: “What’s the status of the purchase of the building from the city?”

I told him we were still working through that, and he said: “I’ll call the mayor and ask him to increase the price for you and then he’ll give it to you.” This showed he had a marvelous sense of humor. He wasn’t known for that, but he had quite a dry wit.

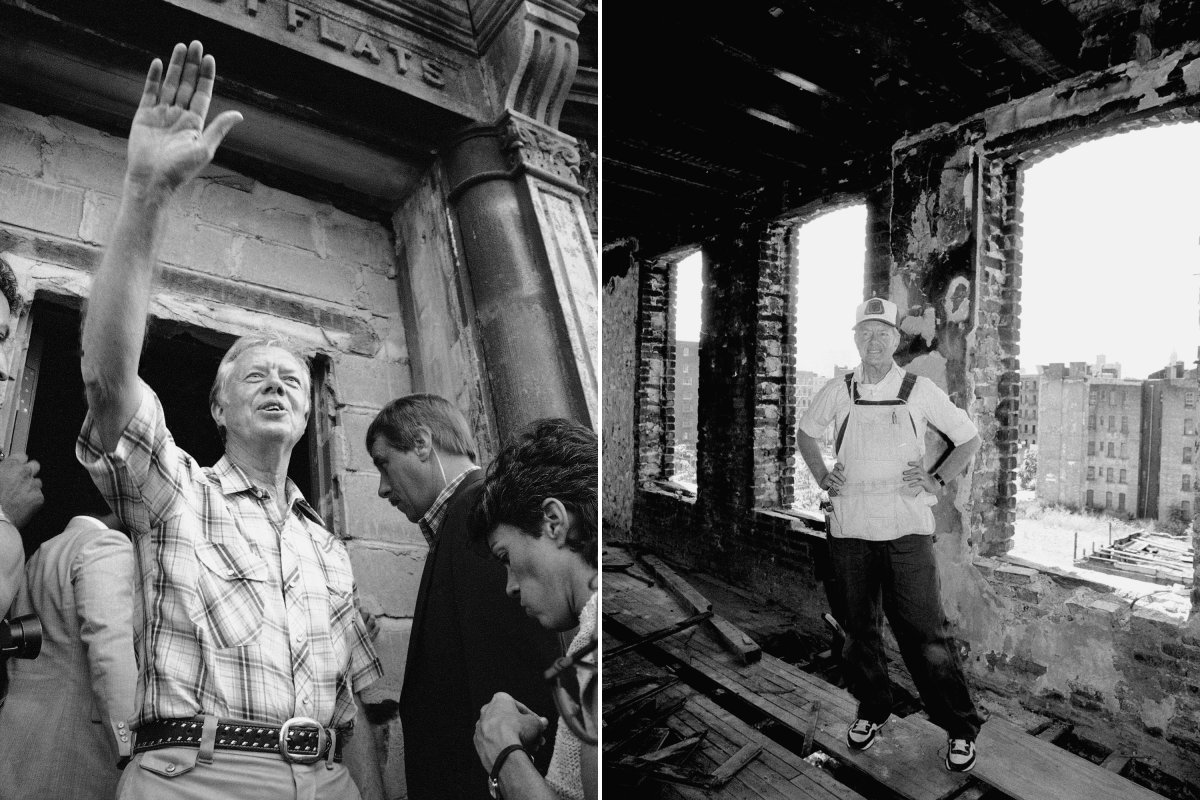

We got down to the Lower East Side, East 6th Street near Avenue D. The Secret Service were going nuts because it was the 9th precinct which at the time had the highest homicide rate in the city, mostly because of drugs. The Lower East Side is nothing like it is now.

Today, my wife and I attend a church in Manhattan and we run into 20 and 30-somethings who come from Kansas City and places like that. They say: “I like New York, but I was hoping to live on the Lower East Side. I can’t afford it. I’m gonna have to live on the Upper East Side.”

In the 80s, when I lived on the Lower East Side, there were three different brands of heroin being sold on my block. It just shows how much New York has changed. (What hasn’t changed is the shortage of affordable housing, more acute than ever).

Before we started work on the building, the junkies had taken the marble slabs out of the staircase. The day before Carter’s arrival, we got volunteers to put together a temporary wooden staircase, but we still had to navigate our way up to the roof, which was full of holes.

From the top, Carter looked downtown and saw the World Trade Center and Wall Street and all that it represented. Then he looked in the other direction, saw Midtown Manhattan and all the wealth and power that it represented.

Finally, peering over the edge to the rubble-strewn backyard of the building, the former president saw an elderly woman cooking her breakfast over an open fire.

That view of the woman stuck with him. He wrote about it subsequently in at least one book, contrasting the image with the fact that he was in the richest city in the richest country on Earth.

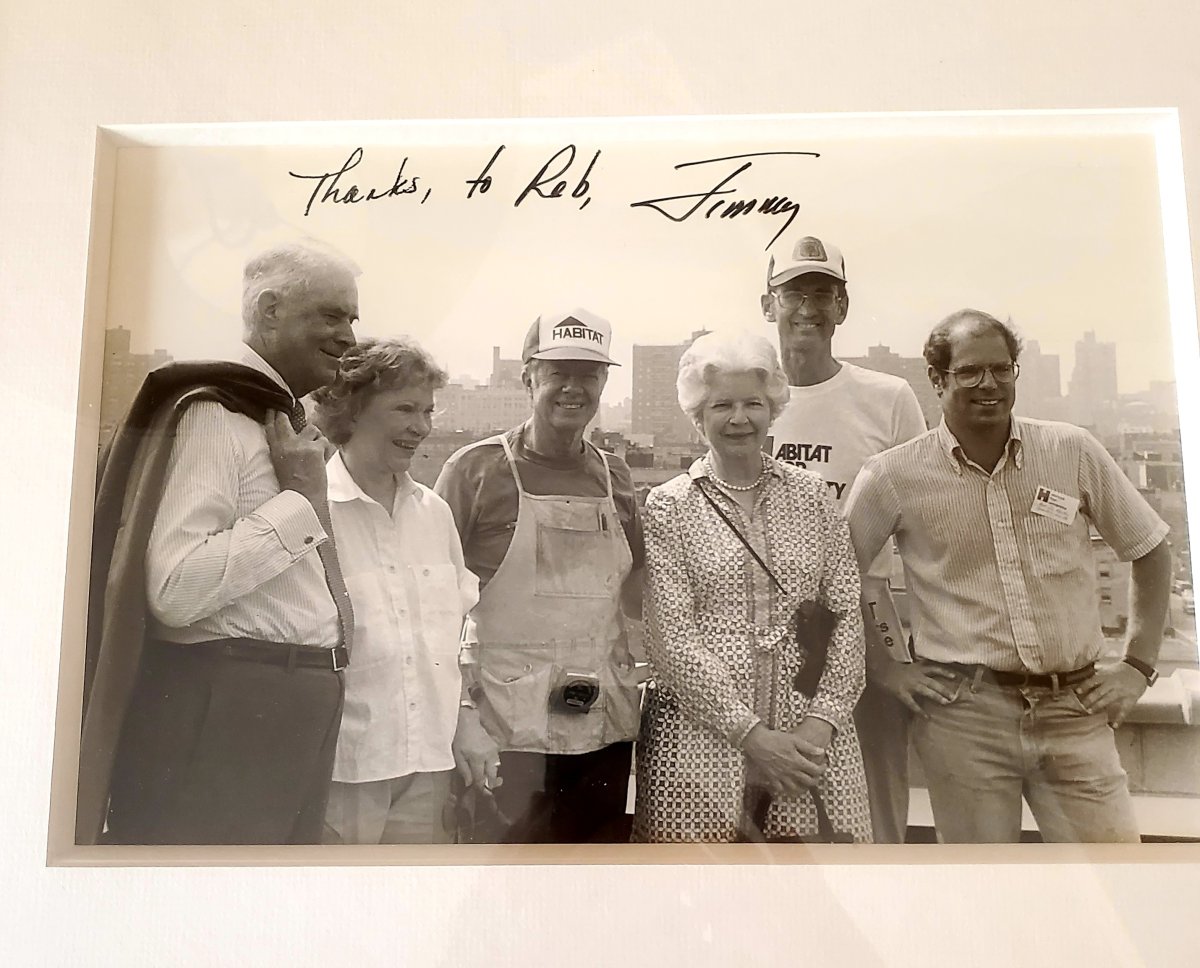

When we got out to his car, Carter said to me: “Rob, Millard Fuller is my boss. If there’s anything I can do to help you here, let him know.”

I blurted out: “Well, maybe you can send up some volunteer carpenters from your church.”

He said, “I’ll think about it,” and the next day he called Millard Fuller and said he was not only going to send some carpenters, he was going to be one of the carpenters. That changed everything.

That was April of 1984 and they made plans to come up in September. They chartered a Trailways bus out of Atlanta, driving overnight to the church I was attending at the time, Metro Baptist on West 40th Street, near the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Hell’s Kitchen.

AP/Mario Suriani/Nancy Kaye

They stayed on bunk beds in the church—including Carter—and then took a bus down to the Lower East Side each day, about a 20-minute ride. He worked throughout that week, but his first day of work was actually Labor Day in 1984.

Labor Day used to be the official kickoff to the presidential race. Both Reagan and Walter Mondale were marching in Labor Day parades, and Mondale was in New York. Meantime, the former president was on the Lower East Side working in a rubble-strewn building.

The AP did a story prior to their coming and the interest exploded. Nowadays, you have sitting presidents working on Habitat projects. Habitat is a major charity today, but back then it was not well known.

The notion that a former leader of the free world would spend an entire week working eight to ten-hour days in a hot building in one of the roughest neighborhoods in New York City was just unfathomable.

The morning shows all broadcast from the Lower East Side. Carter did a press conference that Monday on the steps of the building, but he couldn’t wait to get back to work.

He recognized what his presence would mean for the organization so he was willing to do a few interviews. But his real interest was in the work on the building. He had to be pulled away from the job, being the first to work and the last to lay off.

In subsequent years, I’ve heard he was surprised that a good deal of his image came from the Habitat experience. Maybe he was frustrated because the Carter Center was involved throughout the world in many things, from eradicating river blindness caused by Guinea worm in Africa to monitoring elections.

But he was most famously known for his Habitat work because it’s so visual and dramatic.

Habitat had never done anything like this before, having mostly worked on single-family homes. A 19-unit building in the most visible city in the world was something new, but it instantly put the organization on the global map.

It was also a major fundraising challenge. They were building houses for $30,000, but this thing ultimately cost over a million dollars. That didn’t happen overnight, and things were slow, so Carter came back the following summer for a week.

Carter was a runner, and one day, we actually jogged together from the Metro Baptist building down to the project site, about four miles, which was cool.

Another day, the whole group took the subway and walked through Times Square, then got on the subway and went down to the Lower East Side.

On the subway car, two older women saw him, asked me if that was who they thought it was and said no one in their family was going to believe they had shared a ride with the former President of the United States.

There was a good deal of buzz and it was a heady experience for me as a young man.

Courtesy of Rob DeRocker

I didn’t have any long fireside chats with the former president. Our interactions tended to be more observational and informational than conversational, but he was serious about the work itself.

The second year, it was more finished work rather than gut rehab. This project, started in ’84, stretched into ’86. Early ’86, I saw him at a board meeting. A good deal of his and Habitat’s reputation was resting on this.

When he asked about the project’s progress, I said: “We’re gonna get a certificate of occupancy by June.” He said, “1986?” It was humor with a barb, but we finally got it done and people moved in.

A couple of years later, when he was in Charlotte, I went down to the project while he was there. Carter was sitting under a tree taking a break.

Truth be known, I was a pretty good communicator but not a sterling administrator, and in my mid-20s I hardly knew how to run a project like that. I suspect our nascent board tapped me for the position because I was the only one available— AKA, unemployed. But finally, we got a board that recognized it was time for me to go.

So when I joined Carter in Charlotte I was on the cusp of leaving Habitat, looking to get into journalism or public relations. I asked him if he would write a letter of recommendation. He said no, but that I could give people his name and if anyone called, he would tell them what he knew about me.

That project, more symbolic than anything else, helped launch the visibility of Habitat. It wasn’t going to address the critical housing need of East 6th Street, let alone New York City, but it served its purpose.

Jimmy Carter is often called the best former president we’ve ever had. He’s a man who has lived his faith until the end. The contrast he offers to today’s Christian nationalism and culture wars is stark.

I was a fan of him as president, and I think, like everyone in that exalted position, he couldn’t control everything. He didn’t control the Iranian hostage crisis, or the staggering combination of inflation and unemployment, all that contributed to his being a one-term president.

But of this there is no doubt: He truly cared about the United States and the poor around the world, evident in the Carter Center’s work in Africa and elsewhere.

No politician can suffer from a diminished self-concept and still be in the game, but what I’ve always admired about Carter is his humility.

On the first day of his work on our project, a foreign journalist asked how it felt to be “a former vice president.” Carter smiled and said that having never been a vice president, he couldn’t say. Then, softly, “it shows how fleeting fame is.”

Not long after, he told us about being in Japan and making a speech, leading with a joke. By his admission joke-telling was not his forte, but his led to an extended and surprising round of uproarious laughter.

Carter later asked the translator what he said. Sheepishly, the translator admitted he just told the audience: “President Carter just told a joke. Everyone laugh.”

How many politicians can tell stories like that on themselves? That Carter could is evidence, for me, that his perspective has long been an eternal rather than a temporal one.

And my short time with Habitat and Jimmy Carter was not just a seminal moment in my own life. It reinforced my own Christian faith.

What are the chances that I’d pick up the Daily News that day and see a three-inch squib about Carter coming to New York? I have come to realize there are too many coincidences in my life to regard them as mere coincidences.

Exactly 40 years later, my “accidental” encounter with this remarkable man—and all that followed—remains Exhibit A.

Rob DeRocker is an economic development marketing consultant based in Tarrytown, NY and St. Croix, United States Virgin Islands.

All views expressed are the author’s own.

As told to Shane Croucher.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

“);jQuery(this).remove()})

jQuery(‘.start-slider’).owlCarousel({loop:!1,margin:10,nav:!0,items:1}).on(‘changed.owl.carousel’,function(event){var currentItem=event.item.index;var totalItems=event.item.count;if(currentItem===0){jQuery(‘.owl-prev’).addClass(‘disabled’)}else{jQuery(‘.owl-prev’).removeClass(‘disabled’)}

if(currentItem===totalItems-1){jQuery(‘.owl-next’).addClass(‘disabled’)}else{jQuery(‘.owl-next’).removeClass(‘disabled’)}})}})})