Several Washington Post staffers determined to highlight the richness of their Latino culture decided to share their personal experiences through short essays that might reach your hearts, souls and funny bones.

In one case, a writer describes how the decision by a couple to leave their home country in favor of the United States has influenced the cultural awareness of their descendants. Like so many people through so many generations from so many places, they sought a better life and planted seeds of tradition for those who would come later.

In another essay, sharing a meaningful cultural moment means focusing on an intense love of sports, baseball in particular, and the tremendous satisfaction you can find in selecting the perfect symbol of your true fandom. Another writer shares the deep family unity and strength felt during the funeral of a loved one. And a couple of others present a review of Bad Bunny’s music using the unexpected twist of data analysis.

The author of an essay on yerba mate writes about the drink as a comforting symbol of Latin America. And an essay by another writer familiar with different Spanish-speaking cultures describes the value of embracing the mix in the language, personally and professionally.

We invite you to read these six essays and perhaps connect with some of the experiences found within Latino culture.

The Latino bond

When my parents moved from Mexico City to Los Angeles, they left behind their entire families and some of their cultural ties – even by going to largely Latino L.A.

Like many others, they left their birthplace in search of better lives for themselves and their children. When I turned 23, I too left my hometown, Los Angeles, to pursue a better life. My journalism career took me to Nashville, back to L.A., and then to D.C.

I left home despite objections from my mom, whose eyes filled with tears when she realized my new job opportunity was out of state. But when I reminded her that I was taking a risk much like she had when she left Mexico City, she understood.

Each time I have arrived in a new city, I’ve journeyed to find things that connect me to my culture just enough to soothe my longing. Often, what made me feel most connected was food.

I found a tiny tamal place and then a tiendita selling all the fixings for my ponche navideño, a holiday drink, while in Nashville. And I made my husband turn our car around when I discovered a La Michoacana ice cream shop in Alexandria, Va. These tastes help me feel grounded in unfamiliar spaces.

I realize many people must navigate the duality of being Latino in the United States even if they do not move away from home. I have been fortunate enough to befriend many people who have shown me the richness of Latino culture beyond my Mexican origins.

Latinos make up about 19 percent of the approximately 340 million people in the United States, according to Pew Research. We all have distinct origin stories, but many of us bond and find solace in our similarities.

The bond can come from speaking Spanish, or through music, including cumbia or reggaeton, or through the many food choices. It can also stem from shared experiences with social issues such as racism or prejudice or injustice of any kind. Finally, it can come from the warm embrace you receive when you see a Latino friend.

— Betty Chavarria is a design editor

Magical baseball caps

The 2023 Major League Baseball postseason has brought some thrills, but I’m sure I locked down my No. 1 baseball highlight of the year months ago.

In March, the World Baseball Classic tournament featured a Caribbean bracket based in Miami.

Puerto Ricans, Dominicans and fans of other backgrounds were buying tickets and caps like mad. As an intense fan of baseball caps, and of Puerto Rico, my purchase of the blue cap with the large PR in front and a Puerto Rico flag on the side was a given.

My father is Puerto Rican, and my mother is African American. Growing up biracial and multicultural in D.C. often meant encountering people who tried to guess my ethnic background but were wrong 99 percent of the time.

The PR cap wasn’t only about fashion. It was a problem solver. It displayed my pride in my roots without saying a word.

To my horror, and I’m not playing, there were no caps to be found when I first tried to get one this year. Had Bad Bunny bought them all?

My go-to websites for cap orders? No help. If caps became available, the cost could be double their retail price at about $100 each, if not more.

I thought, watch a Puerto Rico WBC game without a fresh-fitted cap? Not in this lifetime, hermanos y hermanas.

I tried the website of a sports memorabilia store in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York.

The shop came through, but the cap that arrived in the mail was too tight.

“Por qué DIOS? Por QUEEEEEEEE?” Why, God? Whyyyyyyyy?

I ordered a new cap that arrived fitting just right and gave the snug one to my 10-year-old daughter.

When Puerto Rico defeated the Dominican Republic in a game that meant the winner moved on in the tournament and the loser went home, I wore my cap for what must have been at least 24 hours straight. It was magic.

Puerto Rico lost to Mexico in the WBC tournament, which was won by the Japanese national baseball team.

My PR cap, meanwhile, remains a winner. The adventure of getting and wearing it is still my top baseball highlight of 2023.

— David Betancourt is a staff writer

A family, a matriarch, a funeral

My mom had sent the text message at 4:30 a.m. from my childhood home in Minneapolis.

“Tita acaba de partir…” she wrote.

Tita, my 93-year-old grandmother — the anchor of our large extended family in Costa Rica, the stern force of a woman who loved her garden and telenovelas and helped raise eight children, 16 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren — had died.

I called my mom from my apartment in Bogotá, Colombia. The wake would be that afternoon. The funeral would be in about 24 hours.

I had heard about the rushed scramble that is a Costa Rican funeral. In my mother’s home country — and elsewhere in Latin America — funerals take place almost immediately. Public health laws in Costa Rica require the deceased person’s body to be buried within 36 hours.

When someone dies, word spreads fast in this country of 5 million people. The names of the dead are broadcast on TV. Long-lost former neighbors cancel all their plans to make it to a funeral on short notice.

My flight touched down in San José hours after Tita’s death on March 3. Tita, whose full name was María Isabel Jiménez de Arguedas, lay in a casket wearing the pink sweater and gold angel necklace she loved.

I thought about the funerals I had missed during my 29 years. My Tío Fran, who died over a decade ago. My Tío Javi that same year, the day a cousin got married. Some family members went from the wedding to the wake wearing the same suits and dresses.

I had been in Costa Rica for so many planned moments of joy — New Year’s Eve, birthday parties, weddings. I had never been here for the unexpected pain and loss.

I hadn’t realized how much I needed the grieving to feel rooted in this place that is an essential part of me.

As my cousins and I walked behind Tita’s coffin during a procession the next morning, I expected to be overwhelmed by the immediacy of the sadness, by seeing my uncles cry. Instead, I felt grounded.

What a privilege it was to be with them this time, to say goodbye to our matriarch, together.

– Samantha Schmidt is Bogotá bureau chief

Bad Bunny via data nerds

As a couple of Spanish-speaking, music-loving data nerds, it wasn’t enough for us to simply listen to Bad Bunny’s music.

We just had to add some programmatic and statistical sazón to review his lyrics to see what the results would show. We couldn’t help ourselves.

The idea to count how much he uses certain words – quiero, I want, ranks high — felt especially on point considering that the Puerto Rican entertainer released a new album this month called “Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va A Pasar Mañana.”

Bad Bunny, a.k.a. Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, recently has become more prevalent in the U.S. mainstream. This year, he became the first Latino artist to headline the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in California and his “Un Verano Sin Ti” was nominated for a Grammy as album of the year. His relationship with model Kendall Jenner has generated major buzz.

All that made us wonder whether the entertainer, who’s been known in the Spanish-speaking world for several years because of his reggaeton and trap music, might start using more English in his lyrics.

Here’s a brief taste of our first statistical mixtape with samplings of what we found:

Our analysis included Bad Bunny’s first four studio albums, 74 songs in total, which consist of nearly 29,000 words.

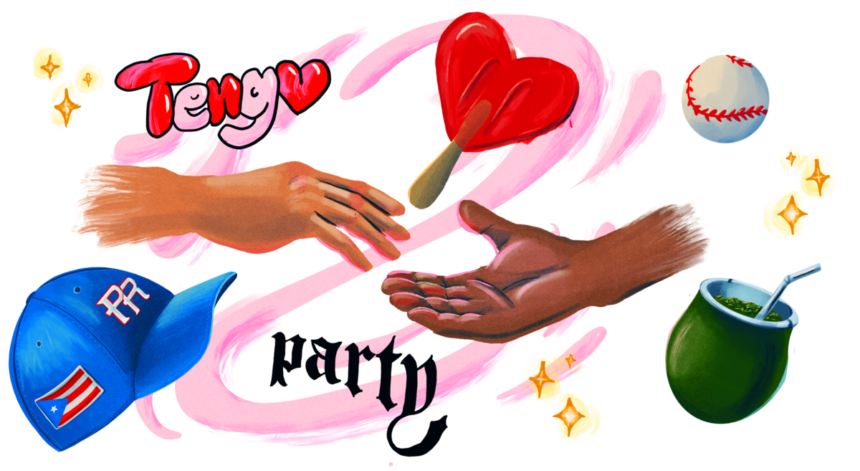

Most of those words — 82 percent — are in Spanish. Tengo, I have, ranks the highest for Spanish words of five or more letters. His most-used word in English is party.

We decided to compare numbers for two other Latino music stars, Ricky Martin and Shakira. Their use of Spanish in early albums never dipped below 88 percent.

After that, they released some albums that had little Spanish, but on their latest albums Martin uses Spanish 90 percent of the time, while 62 percent of Shakira’s words are in Spanish.

We’re figuring Bad Bunny will remain loyal to his Spanish-speaking ways and keep mentioning his cultural pride. As he puts it, now everyone wants to be Latino, “Ahora todos quieren ser Latino.”

– Lucio Villa is a senior software engineer and Emmanuel Martinez is a data reporter

Yerba mate for life

It’s hard to overstate how ubiquitous mate, a traditional herbal tea in Latin American, is in the lives of everyday Uruguayans.

Construction workers take mate, also known as yerba mate, to job sites. Bus drivers tuck containers by their seats. Office employees refill their containers with hot water during breaks. Elite Uruguayan soccer players drink it while playing on European teams, evangelizing the drink among their teammates.

The green, bitter beverage plays an important part in the culture of many South American countries. It appears to have health benefits such as helping to lower bad cholesterol, according to medical research, but also includes a high concentration of caffeine, which is a stimulant and can cause health problems.

Yerba mate came with me when I moved to the United States more than a decade ago. Friends and family often bring me more as gifts. I so appreciate the offerings that remind me of Montevideo, where I grew up.

When I started working in the United States, I often drank mate at my desk. “What is that?” a curious colleague would ask.

I carried my mate as a proud symbol of my identity, yet I felt self-conscious when trying to explain it. The fact that I had to explain it to a colleague reminded me that I wasn’t home anymore.

I remember reading a story about software developers who used mate-infused beverages to keep awake during long sessions of coding.

“Of course,” I thought, remembering those late afternoons and nights I spent studying in college, my mate drink next to me.

The rich tradition passed on for generations in Uruguay has become the equivalent of an energy drink for people in some places. It would be great if more of those people getting a caffeine high from a beverage some influencers call “yerb” could learn about its history.

In the meantime, the drink’s popularity has made my conversations much easier with colleagues, acquaintances and others who are curious about it. When someone asks, “What is that?” I say: “Have you seen those yerba mate drinks they sell at the grocery store? This is the real deal.”

– Maite Fernández Simon is an audience strategy editor

A Spanish-language cornucopia

A teenager in a fishing village in southeastern Puerto Rico posed a question that both stung and amused me.

“¿De dónde tu eres?” she asked, wondering where I was from.

“De aquí, mama,” from here, I replied, despite being raised in the D.C. area, because of my Puerto Rican ancestors.

“Es que tu acento es bien raro,” she said. “Your accent is weird.”

She wasn’t wrong. My Spanish accent is strange. It borrows from various versions of the language, at times blending (some might think mixing up) words popular in Puerto Rico with those from other Caribbean islands or elsewhere.

As Spanish speakers know well, such overlapping of word choices happens in many places, certainly in cities like Washington, New York and Los Angeles, that are home to populations consisting of large groups of Spanish speakers of various origins.

It’s not uncommon to hear someone referring to a car say carro or coche, or someone trying to catch a bus say autobus or camión or guagua. Anyone unfamiliar with the choices might think that a banana is simply a banana, but other possibilities include plátano or guineo.

I dream in Spanish. I pray in Spanish. I think in English, and I write in English.

The curious teenager’s question had unleashed a tsunami of insecurity about my melodramatic relationship to Spanish.

My Puerto Rican mother taught me to read and write in Spanish before I did in English. The rule was Spanish at home, English at school.

My tía, my aunt who was a teacher on the island, taught us the vowels in Spanish and memorizing the Lord’s Prayer in Taino, an indigenous language.

If I wanted to know what chisme, or gossip, the ladies at my largely Salvadoran and Bolivian church were sharing, I needed to keep up. My Spanish included Puerto Rican colloquialisms, Salvadoran sentence structure, and university-level Castilian vernacular.

Little did I know that my phonetic cornucopia was exactly the mix of multilingualism I needed for my journalism career.

It has become a key tool for my mission of telling stories about and for Spanish-speaking communities. In the end, I am understood, se me entiende.