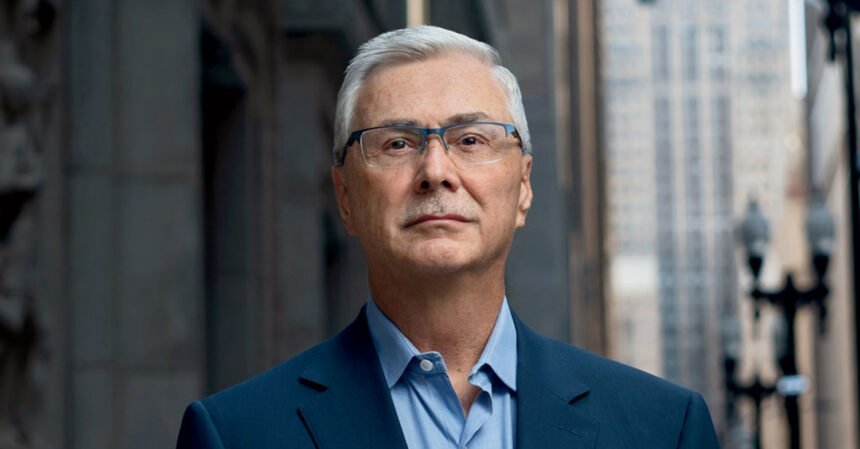

Ralph martire has good news and bad news for Chicagoans whose heads fill with the sound of angry bees upon hearing the phrase “pension crisis.” The executive director of the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, at Roosevelt University, says there is a path to the city funding the $34 billion shortfall in its pension systems. But it requires civic leaders to deliver a delicate message to taxpayers.

The underfunding of the city’s pension systems throughout multiple mayoral administrations has resulted in a slow-building catastrophe. Today, Chicago’s four defined benefit plans for public employees have about $45 billion in liabilities, but only about $11 billion in assets, making the systems uniquely dysfunctional among American cities. In a recent report, the CTBA traced the origins of the underfunding to better understand it and offered a proposal for how Chicago can dig out from its pension debt. Martire sat with Chicago to shed some light on the tricky issues.

Q: What did your analysis find was behind the pension crisis?

A: It’s really not a pension crisis. It has nothing to do with the design of the pension systems themselves or the benefits offered. It is a debt service crisis. For generations, by statute, Chicago was allowed to underfund the pensions. That has created a huge amount of debt owed to the pension systems that compounds interest annually. The big jump in unfunded liability occurred between 2007 and 2020: $22.6 billion. Almost 60 percent of that growth was the statutory allowance for Chicago to underfund its pension. And the reason that legislative rubric was put in place was that the Daley administration wanted to provide services without necessarily paying for them with tax revenue. One way to do that is to defer your long-term obligations. That’s great for taxpayers in the years when you’re underfunding the pension. Not so great later, when you’ve got to make up the difference.

Q: What’s behind the other 40 percent of that growth in unfunded liability?

Q: What cities are handling their pension systems better than Chicago?

A: Most of the nation. The average funded ratio for a public pension plan in America is 78 percent. That means they have 78 percent of the assets that they would need to pay all their benefits if everybody retired at once. Chicago’s systems are collectively funded at about 24 percent, so we are nowhere near any accepted standard of funding.

Q: Do you think public employees who benefit from these pensions have been unfairly cast as villains?

A: Yeah, and it’s really easy to do. There’s a clear ideological worldview that doesn’t like public employee pensions and defined benefit systems. It’s really easy to blame overgenerous benefits and play on people’s biases, because in the private sector most folks don’t have a defined benefit plan. Unfortunately, if you underfund the pensions, then even if you’re generating a decent investment return, it’s not on enough assets. You’re still creating a hole financially that then the taxpayer has to cover.

Q: What is the CTBA’s proposal to fix it?

A: Treat the problem like what it really is. If it’s a debt service problem, why not refinance your debt to save money and still get your funded ratio where you want it to be? We’re saying: Put more money in upfront and flatten out the curve. We found we could save $11 billion between now and the end of the ramp and still get the systems as well funded — actually better funded — as what the current ramp calls for. The only challenge with getting a policy like this done is you do have to put more in upfront. That might mean some minor tax increases plus some pension obligation bonds for about four or five years. But then everybody reaps the benefit.

Q: What is that benefit?

A: It will ultimately make your total tax burden lower and create an environment that frees up revenue to fund current services. Last year, the city had to divert $800 million from the corporate fund into covering the pension. That’s $800 million that, down the road, would be able to go to funding services. It really would make a difference in people’s lives.

Q: Isn’t a tax increase going to be a tough sell?

A: Going to the taxpayers for revenue just to service your debt is somewhat problematic, but we’re going to have to, because [city administrators] created such a big problem over the years. So why not minimize that cost to taxpayers by going now and saving $11 billion over time? Treat your taxpayers as fairly as you can. Make sure that you are freeing up tax revenue to do what it’s really supposed to do, and that’s invest in services and not necessarily handle legacy debt that was created for political reasons. It’s difficult and it would require a lot of political will and support, but I think there’s a case to be made to taxpayers that they would understand. The challenge in the political system is all that short-term thinking. You have to overcome that. You need leadership with a little bit of vision.

Q: You’re a data guy. What are the odds that the City Council would pass such an approach and that the mayor would support it?

A: I don’t speculate. The Center for Tax and Budget Accountability does a lot of things, but speculating isn’t one of them. Not our gig. The way we do our job is not ideological. We’re driven by evidence.

How Chicago Pension Plans Stack Up

The city’s four public employee plans (five, if you include the teachers’ plan, run separately by the Chicago Board of Education) rank as the poorest funded of those in the nation’s six largest cities.

*Funding as percentage of potential payout | source: Equable Institute