Dear Reader,

Let me tell you about where I live.

On my early-morning walks with my Yorkie mix Simba, we often encounter small families of deer, which see so many human walkers and runners in my neighborhood that they glance up but don’t dash away. If I’m not in a rush, I’ll stop to watch geese swim in the two ponds we pass.

My two-story, two-car-garage Colonial home, tucked into a cul-de-sac, sits on close to an acre of land and backs onto a wooded area. My deck wraps around the back of the house with a screened-in gazebo. There’s an unspoken rivalry between the neighbors over who can keep their grass so plush and green it looks like carpet. At night, the sound of the frogs and owls can lull you to sleep.

My “hood” is idyllic, except for one thing.

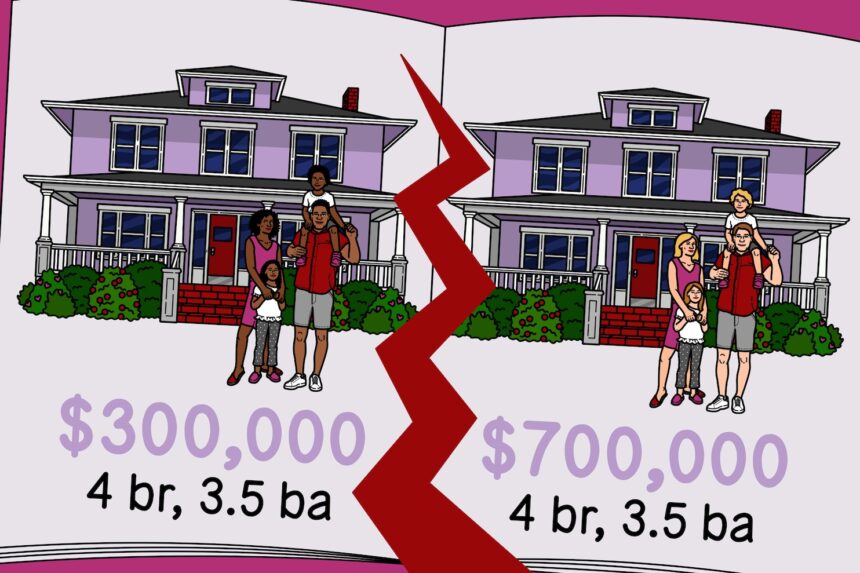

The value of my home in Prince George’s County, Md., would be significantly higher if my husband and I weren’t Black — and if all our neighbors weren’t Black.

Pick up and move our Black neighborhood of doctors, teachers, police officers and small-business owners just 20 miles west to a White subdivision with a similar economic makeup, and our homes would easily be worth 40 percent more. This is true for other Black communities across the country, where homes can be undervalued by as much as 65 percent.

This is the legacy of systemic racism that our government created and, in many ways, still isn’t doing enough to eradicate.

The key to the net worth of most Americans isn’t a stock portfolio but the equity accumulated in their homes. It’s this equity that has created generational wealth for many White Americans. This wealth can fund college educations or finance small businesses. But homeownership, which is so central to the American Dream, has been and far too often remains an unequal and financially frustrating experience for Black families.

The 2019 Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances shows that 45 percent of Black families own their homes, with a median home value of $150,000. That compares with a 73.7 percent homeownership rate for White families, with a median home value of $230,000.

Those gaps — homeownership compounded by home value — are a major reason the typical White family has almost eight times the wealth of a typical Black family. And these gaps are directly linked to “redlining,” which has robbed Black families of generational wealth.

I’ve bought and sold two homes. My husband and I built the home we now occupy with our three children. It infuriates me that homes in nearby White neighborhoods have steadily increased in value.

Federal housing policies starting in the 1930s resulted in a practice of color-coding maps to designate certain neighborhoods as best or worst for mortgage lending. Borrowers buying in White communities — colored green for being safest for lending — could get loans backed by the federal government. Black neighborhoods — colored red — were deemed too risky for mortgage lending. Without the federal guarantee, banks wouldn’t lend to Blacks. Blacks were often forced to purchase homes under predatory contracts that were so financially onerous many ended up being evicted.

In my own journey to understanding the disparity in homeownership rates and home values, I read “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America,” by Richard Rothstein, a distinguished fellow at the Economic Policy Institute. Rothstein traces the roots of real estate discrimination, arguing that for too long we’ve shifted the blame to Blacks rather than own up to the federal government’s significant role in creating a “caste system” that has denied families of color the opportunity to build wealth. Government policy specifically told developers of suburban neighborhoods they could not sell homes to Blacks.

“The maps had a huge impact and put the federal government on record as judging that African Americans, simply because of their race, were poor risks,” Rothstein wrote.

Although the government built public housing complexes to accommodate the need for more affordable housing, it deliberately segregated these communities. And its urban development plans for Blacks lacked the same amenities, funding for schools or access to jobs and other services as public housing built for Whites.

How has your race or identity shaped your financial decision-making? Share your thoughts with us.

One persistent myth about the racial wealth gap is that Blacks have themselves to blame because they aren’t as financially responsible as Whites. But like so many other things — even when controlled for income, education and creditworthiness — homeownership just doesn’t deliver the same wealth for Blacks as it does for Whites.

“Politicians and advocates have long touted homeownership as the best way to build wealth, saying that over the long term, home values go in only one direction: up,” Tim Henderson wrote in a 2018 report for Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts. “But since the dawn of the 21st century, that promise has been an empty one for many African Americans.”

The Stateline analysis of federal data found that in nearly 20 percent of the Zip codes where most homeowners are Black, home values had decreased since 2000, compared with only 2 percent in neighborhoods where Blacks were the minority.

Stop minimizing the damage that has been done by discriminatory housing policies. Maybe then we can agree on remedies — such as funding more first-time-homebuyer programs, which is what I used to purchase my first home.

There’s a significant difference in home values even when a neighborhood consists of affluent Black homeowners. Just look at one wealthy Chicago suburb, the Stateline report says: “Olympia Fields, once a majority-White community and now one of the wealthiest and best-educated majority-Black municipalities in the country, has about the same home prices as it did in 1990.”

Between 1996 and 2018, the median home value in neighborhoods previously labeled as “best” for mortgage lending rose 230.8 percent to $640,238, according to a report by the home-sale marketing company Zillow. The median value in the areas redlined as “hazardous” based on race climbed just 203.1 percent to $276,199.

“It’s a striking example of how discrimination — financial and racial — codified nearly a century ago continues to affect homeowners and whole communities,” Zillow economist Sarah Mikhitarian wrote.

It’s this stark difference in home appreciation that keeps many Whites from buying homes in predominantly Black communities — unless a neighborhood becomes too trendy to ignore. When this happens, home prices soar and become out of reach for many Blacks, who are still dealing with employment discrimination.

Blacks even face higher tax assessments than White homeowners. Black and Hispanic residents have a tax burden 10 to 13 percent higher for the same bundle of public services as White residents, according to a working paper by economists Troup Howard of the University of Utah and Carlos Avenancio-León of Indiana University.

You keep asking me, “What’s your solution?”

The move forward has to begin with you acknowledging that redlining still exists. Stop minimizing the damage that has been done by discriminatory housing policies. Maybe then we can agree on remedies — such as funding more programs for first-time home buyers, which is what I used to purchase my first home.

My husband and I have plans of downsizing one day, and we hope we’ll be able to help our children become homeowners, perhaps giving them enough money that they won’t even need a mortgage. This is what I dream about on my long walks with Simba.

Sincerely,

Michelle