By the middle of the 20th century, Boston Public Schools used a practical, intuitive — and inequitable — system to place students into schools.

Most kids went to class in a building near their home, which meant enrollment mirrored the city’s segregated neighborhoods. Over time, schools became predominantly Black or predominantly white. And the district provided schools that served mostly Black students with fewer resources and worse facilities. Those schools also featured larger classroom sizes and more teacher turnover.

That was the state of affairs in 1972, when Black parents in the city, with the help of the NAACP, filed a class action lawsuit alleging the School Committee was deliberately segregating students by race.

It took two years before federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity would rule on the case and shake Boston’s school systems to its core.

On June 21, 1974, Garrity sided with the parents and ordered the school system to begin desegregating schools by compelling students to attend schools outside their neighborhoods to achieve racial balance.

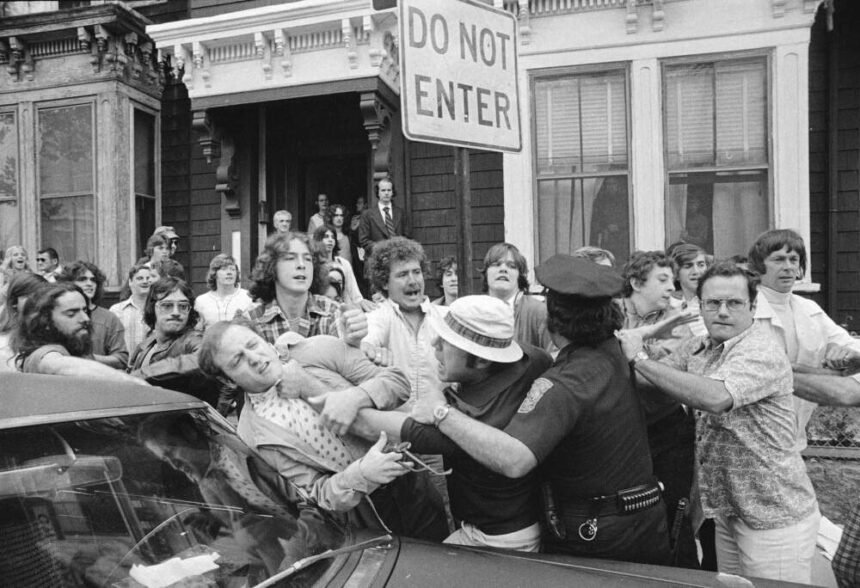

The order — which sparked fiery street protests and accelerated a white exodus from the district — was in place for 13 years.

Fifty years on, the city’s public schools are still wrestling with some of the same realities that drove Garrity to intervene.

In that half-century, Boston has become much more diverse and, on average, more affluent. But its neighborhoods and schools remain stubbornly segregated along lines of race, language and income. And while public school enrollment is less than half the size it was 50 years ago, the district still manages 119 schools thought to be of widely variable quality.

Grassroots efforts to provide students better educational opportunities, like Operation Exodus — a self-funded initiative organized by Black parents to transport Black children to better schools with open seats — gave families some say over where their children go to school. In the latest version of school choice, issued in 2013, limits are set by available seats, home address and the results of a complicated algorithm.

As a result, many Boston students still attend public schools far from their homes, commuting each day by car, public transit or school bus, at the district’s expense.

In the 2025 fiscal year, the district plans to spend nearly $93 million on transportation — more than $2,000 for each of its students, or roughly 5% of its overall spending. But recent expert studies have found that school choice doesn’t make a meaningful difference in equitable access to good schools or academic achievement in Boston.

After busing: ‘Controlled Choice’

Officially, the era of federally mandated busing in Boston lasted from 1974 to 1988.

But local officials began to regain control in January 1983, when the state’s Department of Education was asked to administer the busing policy. Soon thereafter came the city’s first official experiments in school choice.

In the spring of 1985, the Boston School Committee announced that parents who lived within an “experimental district” that contained West Roxbury, Roslindale, Hyde Park and part of Dorchester would be able to rank elementary schools by preference.

At the time, those neighborhoods were at least two-thirds white, scholars Charles Willie and Michael Alves found, and the experiment did nothing to shift the status quo as far as segregation was concerned.

But Willie and Alves also found that the idea of school choice was popular across racial groups.

Three years later, then-Mayor Ray Flynn asked the pair to design a new school-assignment program that would come to be known as “Controlled Choice,” based on a model laid out in neighboring Cambridge earlier in the decade.

According to a 1996 retrospective by Willie and Alves, Controlled Choice in Boston sought to allow parents more options and improve academic outcomes but without resegregating schools.

It divided Boston into three large, heterogeneous student attendance zones, then allowed families to rank schools within the zone in which they lived. The plan’s “control” derived from “racial fairness guidelines,” with each of the district’s racial and ethnic groups being granted proportional access to seats at sought-after schools.

In 1988, less than 15% of Boston’s Black students were in “intensely segregated” schools. By 2003, it had jumped to 50%.

After those guidelines were applied — along with other priorities, including for siblings of current students, bilingual students and those who lived within walking distance — “students are assigned to schools in which instructional space is available and in accordance with their rank-ordered preferences,” Willie and Alves wrote.

In their 1996 analysis, the pair judged that — seven years in — Controlled Choice was working in Boston: it was relatively popular and promoted limited integration. And the model spread to Brockton and Somerville in Massachusetts, and also to Little Rock, Arkansas; Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Seattle, Washington.

Meanwhile, though, the number of Boston students attending racially diverse public schools had already begun to decline — and that trend accelerated into the new millennium.

Boston’s changing demographics played a role in that change, as did decisions by city officials.

In 1990, the federal case regarding segregation in the Boston Public Schools was finally closed. Nine years later, the Boston School Committee voted to abandon any explicit consideration of race or ethnicity in school assignment.

In the following years, Black and Latino students in Boston became increasingly likely to experience “intense segregation” again, according to a 2022 study by MIT economist Parag Pathak and a team at MIT’s Blueprint Labs.

In 1988, less than 15% of BPS’s Black students were in “intensely segregated” schools, defined as those where students of color make up at least 90% of overall enrollment. By 2003, Pathak and his co-authors found, it had jumped to 50%.

Fifty years after the Garrity ruling, Pathak said in a recent interview that Boston’s public school system is confronting very different questions. With Latino students occupying almost 45% of current seats and white students just 15%, “What does integration mean?” he asked.

And having taken part in debates over the design of school-choice systems for decades, Pathak said such questions “distract from the bigger question (of) how do we make all schools better?”

Demographic forces and other busing models

Many forces have contributed to why the district is far less racially divided than it once was.

Most importantly, generations of wealthier white parents have exercised a drastic form of school choice by moving to the suburbs or into private schools.

Already underway by 1974, “white flight” out of Boston (or, at least its public schools) went into overdrive during mandatory busing. Between 1973 and 1978, the district lost over half of its white students — more than 28,000 in total.

Most of the district’s historic enrollment decline happened in the same short period. From a 1973 peak of almost 100,000 students, it had shrunk by a third by 1980, to just over 64,000.

The district has been “majority-minority” ever since, and enrollment has never recovered its previous levels. In 2024, it stands at almost 46,000 students, 73% of whom are Black and Latino.

Meanwhile, some families of color have exercised choices of their own by participating in the long-running METCO program, which carries around 3,000 Boston students to suburban schools; by moving to suburbs; and, more recently, by enrolling in charter schools, which serve more than 10,000 city children.

‘A bold attempt,’ with mixed results

Starting in the 2014-15 school year, the district began to implement the latest iteration of its school-choice system, known as the “Home-Based Assignment Plan.”

This new scheme did away with hard-edged geographic zones in favor of an algorithmic system that generates a list of schools for families based on both quality and proximity. It involves the district ranking schools into four tiers for school quality, based on factors including student standardized scores, school culture and leadership.

When the school committee approved the plan in 2013, then-Mayor Thomas Menino called it “a historic vote [that] marks a new day for every child in the city of Boston.”

Referring to the plan as “a more predictable and equitable student assignment system that emphasizes quality and keeps our children close to home,” he said it “has been a long time coming.”

But Menino’s optimism might have been premature.

For instance, the district sought to keep students learning close to home but also provide them access to quality schools, which are not evenly distributed throughout the city. It aimed to reduce transportation costs without contributing further to racial segregation in the schools.

In a 2018 report, the Boston Area Research Initiative called the home-based plan “a bold attempt to reorganize school choice and assignment to provide students with increased access to good schools, close to home, especially for those students with the lowest level of access.”

But the report concluded that, while students from Black and Latino enclaves could attend a larger total number of schools under the plan, those schools were not necessarily better or more diverse.

That report also concluded that Asian and white students were “increasingly concentrated at a small number of schools that were more likely to be of high quality.”

Northeastern University professor Dan O’Brien, one of that report’s authors, came to see the uneven distribution of high-quality schools in the district as the “unsolvable problem” at the heart of the district’s various experiments in school choice.

“People from predominantly white neighborhoods aren’t faced with a very difficult choice. There are good schools near their homes, and chances are they’ll get into one,” he said.

Students of color, on the other hand, “tend to live in areas with fewer high-quality schools,” he said. “They’re faced with a choice between ‘quality’ or ‘close to home.’ ”

Still today, in 2024, higher-needs students — as well as Black and Latino students — remain disproportionately enrolled in schools that the state and, to a lesser extent, the district itself deem to be of lower quality.

For instance, the 2018 report noted that Boston’s “southern core” — from South Boston to Roxbury, Mattapan and Dorchester — have “very few Tier 1 schools nearby.” Black and Hispanic kids who predominantly live in those areas have to travel longer distances to attend Tier 1 schools and compete more intensely for seats, the report said.

Meanwhile, white students made up just under 15% of BPS enrollment, but 24% of enrollment at Tier 1 schools. And Black and Latino students — 73% of the entire district — comprise 84% of the enrollment at Tier 4 schools.

The 2018 report came to a frustrating conclusion: even well-designed efforts can be thwarted by competing political priorities — and a segregated city.

“Simply put, it is impossible for a choice system to provide ‘quality schools, close to home’ if there are no quality schools nearby in the first place,” it concluded.