What exactly is art; who defines it; who makes it, and where in Atlanta do poets, thespians, and artists congregate and create? We’ll use this space to catch up with a few…some you may know; others we hope you’ll be pleased to make their acquaintance.

The first camera I ever owned—excluding my Fisher-Price and my Kodak Instamatic in 2nd grade—was a 1970s-era Mamiya/Sekor 1000 DTL, a gift I “found” after dusting off my father’s photography equipment when I was in college.

Like Richard E. Watson’s mom, my father was the family archivist, leading to a photographic chronology of my childhood as well as awakening a curiosity in me that only grew. In fact, my first mentor who taught me how to use that Mamiya/Sekor was a high school classmate, Arnold Sinclair who went on to become a cameraman at WSB-TV until his passing last year. Arnold’s eye helped train mine when it came to composing a shot.

The first camera I ever purchased was a used Canon AE-1 Programmable. This led to classes at the old Showcase Photo on Cheshire Bridge Road and hundreds spent at the old Wolf Camera in Virginia-Highland. However, at some point in my struggle to determine the correct aperture and lighting, I realized I was not the next Arbus or Weems. But in interviewing Watson, I realized one of the most significant gifts my father, who passed away in 2023, gave me—besides his camera—was his love for images, language, and, like Watson, jazz. And these gifts shaped my perspective on the world, helping me to find and define the beauty in it.

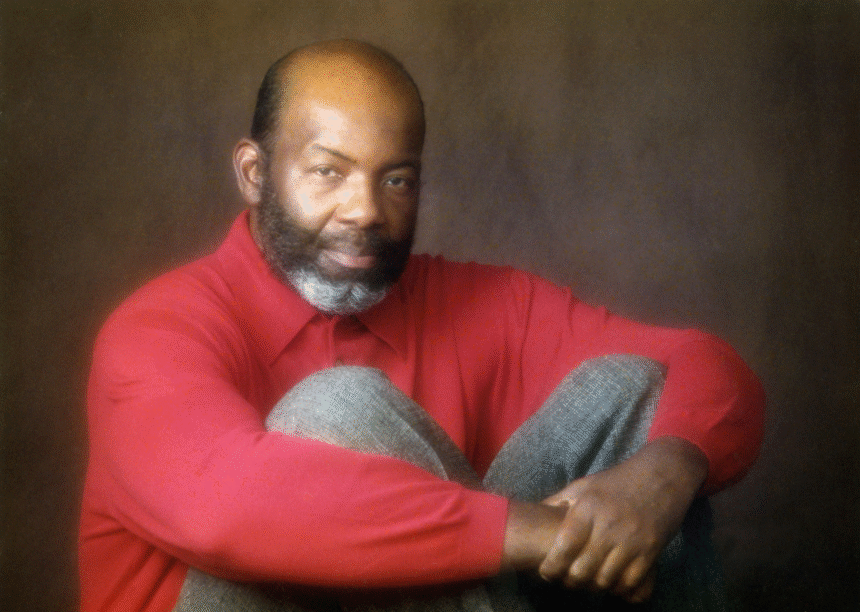

But as for photography, I now leave it to true artists like Watson, a modern equivalent of Monet in this medium. A born-and-bred Atlantan, he also uses the city as a canvas, character, and close companion in his creative process, with many of his gallery images captured here. He is an avid traveler and has shot in cities from New York to San Francisco, as well as across the lush and majestic landscapes of Hawaii, the Caribbean, and Europe.

In Watson’s downtime, he and his wife, Margaret, like to attend events at City Winery, the Blue Note in Duluth, Mason Fine Art Gallery, Alliance Theater, and the High Museum of Art, where they are longstanding members.

Richard, when did you fall in love with photography?

Great question! My love affair with photography began when I was very young, around ten or eleven years old, and I found my inspiration in my mother. My mom was the family’s self-anointed lens person. She succeeded in memorializing all of our family’s history through events such as holidays, birthdays, graduations, Easter, weddings, and picnics in pictures. During those early years, I didn’t realize the effect that her persistence with picture taking would have on me until after I graduated from Morehouse in 1968, served in the Army, and obtained my MBA from Atlanta University in 1972.

I have always been a creative, visual person. In my youth, I often found myself drawing and sketching without any formal guidance or structured tutoring. Even though my interest in photography waned at one point, fate would have it that I later traded some stereo equipment a friend wanted for the camera he no longer needed. It was 1970, and my world was about to change in ways I’d never imagined. It was also the beginning of my photography career. My creative energies soared, and I was producing images of anything that would stand still for five seconds. These early years of trial and error would eventually yield measured success by the early 1980s, and it was then that I knew it was what I was meant to do.

How has photography shaped your creative expression and storytelling, and what keeps you committed to film over digital today?

In the late 1970s, I took night classes at the Art Institute of Atlanta, where I learned essential film photography skills, including the art of black-and-white processing in the darkroom. I’ve stayed committed to photography as it allows me to express my creativity in ways I never imagined. Through photography, I can visually communicate my perspective on people, places, and their connections.

I am inspired by a range of ideas and aim to create relatable stories and imagery that is both unique and deeply relatable. I am forever seeking something I’ve not seen before. It’s my way of continuing to work with intention and produce inspirational images.

When it comes to aesthetics and technique, I find digital and film photography similar but beginning with film shaped my creative process in ways that still influence me today. For me, working with film provides a hands-on experience that enhances my skills beyond what digital photography offers. Film has made me a better photographer, but ultimately, the choice between film and digital is a matter of personal preference.

How has the evolution of film photography affected your approach and choices and what are your thoughts on its relevance in today’s digital age?

In my early photography years, I used both color and black-and-white print film. By the mid-1980s, I was introduced to the technological magnificence of color reversal film. Since then, I’ve stopped using color print film. It simply doesn’t provide the quality results demanded by photographers, particularly those working in the genre of fine art photography.

There has been a resurgence in demand for high-quality color and black-and-white film recently, leading to rising prices. The debate continues over whether Color Reversal film is equal to or better than digital, but I believe it rivals, if not surpasses, higher-end megapixel digital cameras. I’ve used color reversal film for decades for its tonal range, color saturation, contrast, and grain structure. For black and white, I now exclusively use Ilford’s Delta 100 for the same reasons.

Your body of work is absolutely gorgeous—I especially love your water lily series. What series of images would you consider your defining work or want to be your artistic legacy?

Thanks so much for that question. I have hundreds of unpublished images that may or may not be posted to my website. However, those that are on the website should be considered some of my best work. When I consider legacy images, they include the following:

- Self Portrait: Provides a succinct characterization of my photographic “style”.

- Times Square: Captures an abstract visual interpretation of the energy and movement of Times Square.

- Reflections: A closer examination of the abstract reflective properties of metal, glass and water.

- Barcelona: Showcases abstract street scenes of Barcelona’s urban sophistication

- Chasing Water Lilies: Simple fairy tale of children exercising their boundless curiosity chasing a seemingly elusive collection of water lilies.

How have you navigated the evolving art world to showcase your work, and what five items would you leave in a time capsule to help out a photographer just getting started?

Most artists, regardless of their genre, aim to share their work with a larger audience. However, achieving this goal can be more challenging than it may seem. Over the years, the art world has evolved into a vast industry driven by art dealers, gallery owners, exhibition curators, art critics, and other professionals. The creation and value of art do not rely solely on its aesthetic quality; they are significantly influenced by effective marketing strategies. For artists, navigating the complexities of the art world can be difficult.

Over the years, my work has been primarily showcased through group exhibitions. Proudly, I’ve received several awards for those efforts. Moving forward, I plan to sponsor my own solo exhibitions with the aid of social media and my current affiliation with the Atlanta Photography Group (APG), an organization dedicated to exposing the work of its members to local and regional artistic support organizations. We’ll see how it goes.

In the meantime, here is what I would leave in a time capsule for a future photographer:

- A copy of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s book “Europeans,” a biography written by Jean Clair of one of the twentieth century’s most influential and original photographers

- A vintage Nikon F2 Photomic 35mm camera w/85mm f2.8 Nikkor Portrait Lens. I had one that I cherished but unfortunately was stolen back in the eighties

- Photography for Dummies (the most recent edition)

- A copy of Gordon Parks’ “Segregation Story,” a beautiful book compiled by the Gordon Parks Foundation, which documents the daily realities of African Americans living under Jim Crow laws in the deep South during the 50s and 60s. Gordon Parks is an icon and one of my favorite photographers.

- A good tripod.

To learn more about Watson and his work, check out his website.