Earlier this year, Bad Bunny was asked on Popcast, The New York Times’ music podcast, if he was worried that people wouldn’t understand his lyrics. In response, the most-listened-to artist on the planet explained that even some Spanish-speaking Latinos don’t get his lyrics, because he sings in Puerto Rican street lingo. When asked if he felt the need to explain his songs, the 31-year-old artist, whose real name is Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, hummed “I don’t care!” which has become a mantra for many of his fans.

Bad Bunny’s stance of making Latino culture and the Spanish language stand alone transcends personal preference and acquires a clearly political connotation framed within the current U.S. context. After Donald Trump’s return to power, official communication channels in Spanish were eliminated and federal agencies were no longer obliged to offer assistance to people who do not speak English. Currently, 90% of those detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) are Latin Americans, according to the Immigration Justice Campaign.

Bad Bunny considers singing in his own language the obvious thing to do given that it is the language he thinks in, making it an essential part of his identity. In a memorable appearance on Saturday Night Live in October, in reference to his long-awaited and controversial appearance at the Super Bowl halftime show next February, the singer said, “If you didn’t understand what I’ve just said, you have four months to learn.”

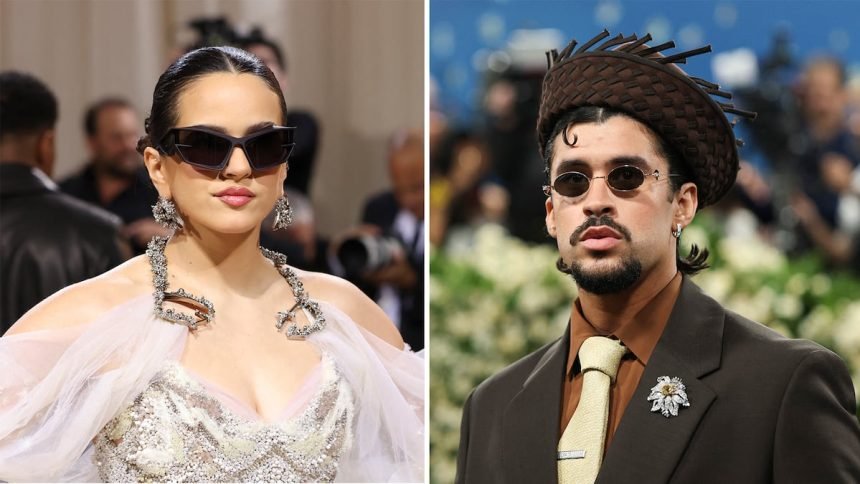

Alluding to the same question on Popcast, Rosalía said, “I think I’m the opposite of Benito. I do care. It matters so much to me that I make the effort to sing in a language that is not mine, even if it is not within my comfort zone.” Although apparently unintended, her response was interpreted as confrontational by the Spanish-speaking public and sparked online furor.

The singer herself addressed the controversy early November by responding to a video posted on TikTok. The video accused her of benefiting from Latino culture without understanding its background: “The reason why [Bad Bunny] decides to only sing music in Spanish is because he’s standing up for his culture. Something you cannot relate to because, what? You are not a Latina, you’re a Spaniard. He’s standing up for something that you just don’t get,” the TikToker added. “You are not a Latina, yet you have benefited from Latino culture. So you should be able to stand up for it. But it does not surprise me that you’re just like, ‘Not my circus, not my monkeys.’”

In a comment that she later deleted, Rosalía replied: “Hey, I understand your point of view but I think it’s being taken out of context. I have nothing but love and respect for Benito, he’s a great colleague that I admire whom I’ve been lucky to collaborate with. (…) I’ve always been grateful to Latin America because, despite coming from another place, the Latino people have always supported me throughout my career and I empathize with what you’re explaining. Precisely for that reason, it saddens me that this is being misinterpreted because that wasn’t the intention.”

On October 27, Rosalía released Berghain, the first single from her fourth album, Lux. Released on November 7, it is an album of female mysticism in which she sings in 13 languages, including Ukrainian, Catalan, Sicilian, Mandarin, Arabic and Latin. “I belong to the world. The world is so connected. Why would I put a [blindfold on my eyes]. It don’t make any sense,” explained Rosalía, who says she has devoted an entire year exclusively to the lyrics on the album.

At the end of the 1990s, Latino and Hispanic artists who wanted to make their way globally were forced to sing in English, or mix the two languages. This was the case for Ricky Martin, Enrique Iglesias, Shakira and Marc Anthony, architects of the Latino music boom. Then there have also been English-speaking artists trying out Spanish. Spanish is the second most spoken language in the U.S. and many artists have sought to reach the Spanish-speaking community, recording albums in both languages; think Jennifer Lopez, Christina Aguilera and St. Vincent.

The debate on whether or not to record in a language other than Spanish dates back to the early 2000s. When Shakira began to sing in English, her fellow Colombian singer Juanes turned up at the Latin Grammys and the MTV Awards wearing a T-shirt that read “Se habla español” (We speak Spanish). At that time, he was promoting his album Mi sangre, which included songs that achieved global success such as La camisa negra. Other Hispanic artists, such as Alejandro Sanz, Luis Miguel and Chayanne, never felt forced to record an entire album in English.

“Latino artists have been progressively gaining greater autonomy while genres such as salsa have ceased to be mere entertainment and now play a fundamental role in how the Hispanic community is recognized,” writes Eduardo Viñuela Suarez, a professor at the University of Oviedo in Spain, in his article Pop in Spanish in the United States: A Space to Articulate Latino Identity. According to Viñuela Suarez, the 1990s boom marked a turning point in the history of Latino music and came to reflect a more integrated and better positioned Hispanic community within American society. “Besides breaking records on platforms such as Spotify and YouTube, the new generation of Latin musicians is being recognized at the Grammys and occupying prominent places at major festivals, such as Coachella, as well as in high-profile events such as the Super Bowl,” he writes.

“At the end of the day, I’m Latino. … I think that if I’m myself, I can conquer the world being myself and singing in Spanish,” Maluma said in an interview on CBS prior to his performance at the 2020 Global Citizen festival, where he was the only artist who did not sing in English. The Colombian artist pointed out how exciting it is for him to sing in non-Hispanic countries and see how 30,000 people sing along to his songs in Spanish. It is an experience similar to the one Ricky Martin lived when he sang La copa de la vida, the song he wrote for the World Cup in France in 1998 and which was number one in 70 non-Spanish-speaking countries. “Imagine what it’s like to go to New Delhi and see 50,000 people in a stadium singing in Spanish? For me it showed you can conquer the world without singing in English,” the Hispanic star said.

“I think the English-speaking public is more open to Spanish lyrics,” Félix Contreras, co-creator and co-host of NPR’s Latin music podcast, Alt.Latino, told EL PAÍS. “How many non-Spanish speakers did you hear sing “Deeespaaaaciiito” in the summer of 2017?”

Unlike the first boom more than three decades ago, the current phenomenon is marked by artists who assert their identity by singing in their own language. They no longer feel the pressure to adapt to English to conquer new markets; on the contrary, they expect the public to accommodate them. This is how artists such as Bad Bunny and Maluma, are thinking; also Karol G, Residente, Natti Natasha, Nicky Jam, Becky G, Bomba Estéreo and Silvana Estrada.

“Young artists do not face the same obstacles in sales and audience as Latin artists did in the 1990s,” says Contreras. On the other hand, the approach to English lyrics, if there is one at all, no longer involves recording two versions of the same album, but rather merging Spanish and English languages in a single song or collaborating with English-speaking artists. This creative convergence has allowed Spanish-language music to cross borders and be normalized on the international stage.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition