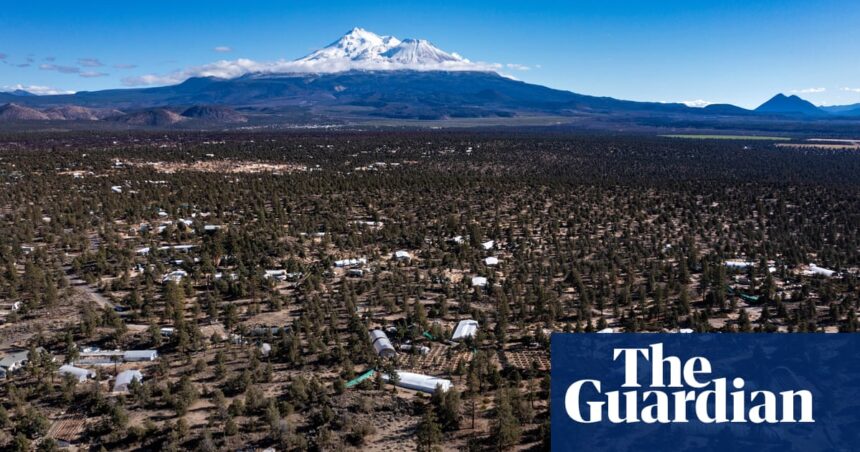

In the shadow of Mount Shasta in northern California, a sea of makeshift greenhouses and plywood huts sprawls between the conifer trees of the high desert. From the air, many of the polytunnels look in bad shape, their plastic covers torn by the wind to reveal what’s inside: hundreds of cannabis plants packet tightly together, their distinctive green leaves easily identifiable against the volcanic soil.

This remote area of Siskiyou county is known for its goldrush history, black bears and returning grey wolves, but in the last few years it has also become a hub for California’s parallel market in cannabis production. More than 6,000 hectares (15,000 acres) of illicit cannabis farms cover the Republic-leaning county, which voted not to legalise commercial farming despite the statewide vote for legalisation in November 2016.

Several thousand people are thought to be living in the seasonal encampments where illicit cannabis is grown near Mount Shasta, often without an official connection to water or sewage supplies. Many producers are Hmong Americans, and tensions have erupted with law enforcement over water access, prompting accusations of racism. Trucks transporting millions of dollars worth of cannabis have been stopped on the highway, and there is growing concern among authorities about the consequences for the surrounding ecosystem.

As legalisation has spread around the world and governments increasingly treat the plant like any other crop, attention has turned to the environmental impact of cannabis. The plant is often energy intensive, can lead to intense use of pesticides, and is another unwelcome demand on scarce water in some regions.

A 2012 study estimated that 1% of US electricity was used for cannabis cultivation, rising to 3% in California, according to a separate study. No estimates exist of the land footprint of cannabis production but there is evidence that weed growing has become a new agricultural frontier. A 2018 study on two counties in California found that nearly 90% of farms were constructed in natural areas, most commonly on forest.

Some of the environmental concerns apply to both the expanding legal sector and the black market, but researchers say there are differences between the two. In California, legal growers in the commercial industry – worth an annual $5bn – must follow strict rules. No such rules govern the hidden market.

The wilderness around Mount Shasta is protected by law, sheltering spotted owls, Pacific fishers and rare plants such as the Shasta owl’s clover. The Medicine Lake Volcano, 30 miles from Mount Shasta, is an important drinking water resource for the state that captures snowmelt from the surrounding area.

“We’ve gone down there on the ground and there’s really no wildlife. You’re lucky to find a lizard,” says Rick Dean, the community development director for Siskiyou’s environmental health division. Along with helping local people rebuild from the region’s enormous wildfires, Dean is spending ever more of his time on the consequences of illegal cannabis production.

One of the challenges is “the daily accumulation and disposal of human waste and garbage that is buried on site. Many are plastic containers left over from fertilisers and pesticides.”

When California voted to approve the use, sale and cultivation of marijuana, many argued that a tightly regulated industry would see the illegal trade squeezed out. Eight years later, the multibillion-dollar illicit market is thriving while the regulated system struggles.

Illegal production continues on federal land and forest ecosystems, sometimes with links to organised crime groups. There are fines for illicit growers but most amount to a few hundred dollars, which authorities say is little deterrent. By contrast, commercial growers in the legal market are obliged to follow restrictions covering the use of pesticides and chemicals, with dispensaries testing cannabis products before they go on sale.

Standing on a hill looking over the makeshift greenhouses and partially buried rubbish, local sheriff Jeremiah LaRue says authorities do not have enough resources to clear the illicit operations. Pickup trucks can be seen patrolling the site. “There’s a lot of concern about environmental damage. We see the labour trafficking of the people that come in here and work; water use concerns; and the marijuana is essentially being cultivated with pesticides that are not supposed to be on the plant.

“The marijuana goes to anywhere … to licensed facilities. We’ve tracked it to other states. It’s a public health issue,” he says.

While his team do issue fines after raids, they largely go unpaid. When a growing site is abandoned or cleared, Siskiyou county estimates the cleanup costs to be about $30,000 an acre, with workers routinely finding illegal pesticide that could be fatal to people who breathe it in.

“The idea was that [legalisation] would combat the illegal side of things,” says LaRue. “This exploded around the same time as legalisation. All the costs associated with doing it legally are way more than to do it illegally. It’s not about whether the plant is bad. If this was corn, or strawberries, or cherries, whatever, it would still be wrong.”

While research on cannabis production is limited, some experts say the environmental impact is being overstated. In some areas of California, it has been associated with forest fragmentation, and studies have found that intense water use sometimes has knock-on impacts for freshwater ecosystems. The use of herbicides, insecticides and rodenticides, especially with illegal cultivation, pose a risk to water quality, research indicates. But with such limited funding for research, the full picture is unclear.

At Goldenhour Collective cannabis dispensary in Weed, California, a short drive from the network of illegal grow sites, gummies, vapes and glass jars of marijuana to smoke line the shelves. The independent store caters for both medical and recreational use, explains the assistant, Lauren, but regulation of the legal market makes it difficult to run a business.

“California makes everything hard for owners and most small businesses to actually operate. They put regulations on top of regulations. The way they’re going, they’ll run marijuana companies out of business,” says Lauren

“For us, and all the legitimate enterprises, you have to get the cannabis tested three times. It has to be pesticide free to stop people ingesting something that could be harmful.”

Many in the industry raise concerns about California’s Department of Cannabis Control, the state regulator, warning that it is underfunded and does not take seriously issues with the hidden market. The department says it routinely carries out enforcement operations, including in Siskiyou county, and has seized about $60m worth of illegally grown cannabis in 2024, arresting 12 people. In 2023, it seized $424m of cannabis and eradicated 403,644 plants, making 100 arrests. It will release a report estimating the size of the illegal market next month.

Due to federal restrictions on funds for universities to study the newly regulated industry, little is yet known about production in California’s legal cannabis sector. A 2018 survey of growers was among the first to give an idea of the structure of the legal industry, finding that most produced outdoors or in greenhouses and used biologically based pest control, such as insect predators that eat pests.

Houston Wilson, a University of California, Riverside researcher who led the study, said the hidden market is just one side of the story, and many in the legal trade are striving to produce cannabis in the most environmentally friendly way possible. “Cannabis does not inherently have more environmental impacts than any other crop produced in this state,” he says.

“I don’t think there’s a lot of people spraying crazy amounts of insecticides secretly. There’s truly a very motivated group of growers who want to communicate how sustainable these systems can be.

“What fraction are like Siskiyou, and what are like some of the stuff I’ve seen in other parts of the state, where it’s all organic? We don’t have a good handle on that.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on X for all the latest news and features