Black and Latino households spend a greater portion of their income on paying for energy, studies show. In Boston, Black renters spend 11 percent of their income paying for energy, compared to the city average of 7 percent, according to a 2024 report from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

Several reasons fuel these disparities, but they often boil down to deeply rooted systemic barriers, says Hessann Farooqi, the executive director for the climate justice advocacy organization Boston Climate Action Network. Many homes in Boston are old, he said. They are less energy-efficient and use older appliances that use more fuel to do the same amount of work as newer appliances. But this is especially true in communities of color.

“The average quality of housing that Black Bostonians are living in is less good than the average home that white Bostonians are living in due to, in part, generations of residential segregation and disrepair for some of those homes,” Farooqi said. “And that directly translates to higher energy bills.”

Notably, the lingering effects of the 20th-century practice known as redlining still permeate homes in certain Boston neighborhoods. With redlining, real estate professionals color-coded maps of cities in order to racially and ethnically segregate home buyers. Neighborhoods outlined in red were often neglected for generations. People who live in formerly redlined areas sometimes still grapple with redlining’s structural and environmental impact. In the summer, for example, formerly redlined areas in Boston are hotter than non-redlined areas.

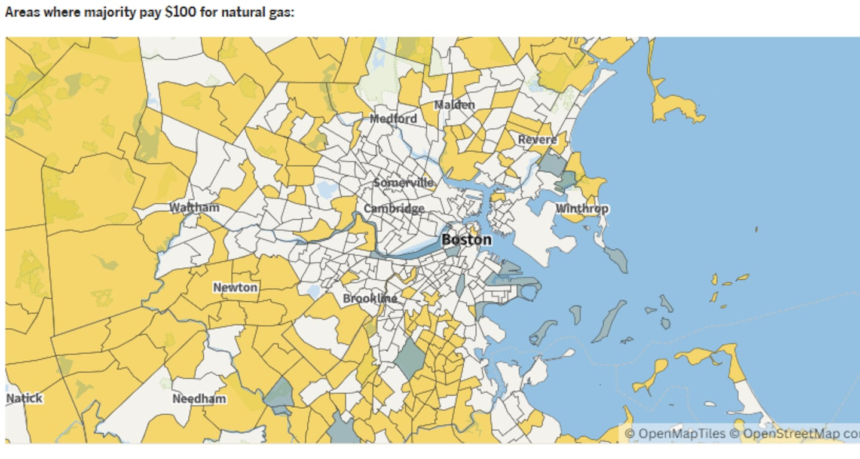

On a map, many of the parts of Boston where most people are paying $100 or more for gas are concentrated in neighborhoods such as Dorchester and Roxbury. Areas where people aren’t paying that much are in communities closer to Downtown Boston, including South Boston and East Boston, which have seen a recent explosion in new development.

Tony Reames, a University of Michigan environmental justice professor and former Department of Energy senior policy adviser, has spent most of his career studying racial and economic disparities surrounding climate and clean energy. His research shows part of the reason Black and Latino neighborhoods pay more for energy is that their homes often are not as energy-efficient.

“That has a direct connection to the amount of energy you consume, which then has a direct connection to your monthly costs,” Reames said.

People can lower their energy bills by making their homes more weatherproof and sustainable. Both Farooqi and Reames point to programs like Mass Save and the Weatherization Assistance Program designed to help residents make their homes better equipped for saving energy. But this comes with a host of obstacles.

Even with programs such as Mass Save, which helps pay for heating and cooling upgrades, many people in Black neighborhoods don’t get to participate due to barriers like being renters instead of owners or living in multifamily homes, which are often restricted, Farooqi said. ”We know, unfortunately, from years of research that so many of our Black and Brown neighborhoods are paying more into these programs than they’re getting out,” Farooqi said. “And these programs are just not designed in a way that works for the kinds of homes that we have, broadly, but especially in these Black and brown neighborhoods.”

In cases where Black residents are homeowners, they might still be hesitant to participate in these programs, Reames added. “That’s another challenge: Everybody doesn’t want to participate in social service programs or don’t think they qualify for it.”

Landlords also pose a challenge. There is usually little incentive for landlords to make homes more energy-efficient when tenants ultimately benefit from the upgrade at the owners’ expense. This so-called split incentive between landlords and tenants makes it difficult to get old apartments in large cities upgraded. It can be costly in the short run, Farooqi said, but he thinks landlords have a responsibility to switch out old systems for newer, efficient ones. For those who can’t afford it, he calls for the government to help.

“Let’s also acknowledge that not every landlord has a bunch of disposable income in the bank. It’s often the largest ones. They need to make those investments themselves, and laws need to be passed to make that happen,” Farooqi said.

The state offers various rebate and incentive programs for homeowners. This includes incentives for upgrading to electric energy and adopting heat pump systems. But Reames and Farooqi said startup costs and early rates are intimidating to many homeowners. Today only 20 percent of households in Massachusetts use electricity to heat their homes, compared to 42 percent of households in the country.

Environmental disparities have been a decades-long challenge with an uncertain future. During his time at the DOE from 2021 to 2023, Reames hoped to expand the office’s mission into the future, spearheading the office’s program that directs 40 percent of certain federal clean energy investments to disadvantaged communities.

But it’s unclear if environmental justice will remain a national priority. Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s 900-page unofficial playbook for the incoming executive administration, calls for getting rid of all energy justice programs (President-elect Donald Trump has distanced himself from the project, but has nominated some people associated with it for his Cabinet).

“I remain hopeful,” Reames said. “I think issues of affordability and issues of access for all are non-partisan, and people should still be able to do that work, because we’re talking about public dollars and the public good.”

This story was produced by the Globe’s Money, Power, Inequality team, which covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston. You can sign up for the newsletter here.

Vince can be reached at vince.dixon@globe.com. Follow him @vince_dixon_.