Hundreds of years before there was the American cowboy, there was the vaquero, an expert horseman who could adeptly herd cattle and whose skills with a lasso were legendary.

First trained by the Spaniards who arrived in 1519, on land later known as Mexico, the original vaqueros were largely Indigenous American men who were trained to wrangle cattle on horseback. “It’s a forgotten history of centuries of horsemanship in the Americas that root the vaqueros to the colonial past,” says Pablo A. Rangel, an independent historian who has extensively studied the history of the vaqueros.

Derived from the word vaca (Spanish for cow), the vaqueros would become renowned for their skills and adaptability as Spain expanded their North American empire westward from what is now Texas, Arizona and New Mexico to the Franciscan missions in California by the late 1700s. In the years before cattle branding and modern ranching styles became prevalent, Rangel says, the work of vaqueros was essential in a society where food supplies were often scarce and the cattle imported from Spain often broke free.

Spanish Ranchers Bring Cattle to Texas

While Spaniards had always had a long tradition of horsemanship, life on the rugged North American terrain required something more. “What separates the vaquero from just a horseman is that they braided rope. They built their own saddles,” says Rangel. Most importantly, “they were able to tame wild horses and they were throwing the lasso.”

The Indigenous Roots of Vaqueros—and Cowboys

While classic Westerns have cemented the image of cowboys as white Americans, the first vaqueros were Indigenous Mexican men. “The missionaries were coming from this European tradition of horsemanship. They could ride well, they could corral cattle,” says Rangel. “So they started to train the native people in this area.” Native Mexicans also drew on their own experiences with horsemanship and hunting buffalo in order to refine vaquero techniques further, says Rangel.

In addition to herding cattle for Spanish ranchers as New Spain expanded westward, vaqueros were also enlisted as auxiliary forces in skirmishes between native communities and others.

The Emergence of Vaquero Culture

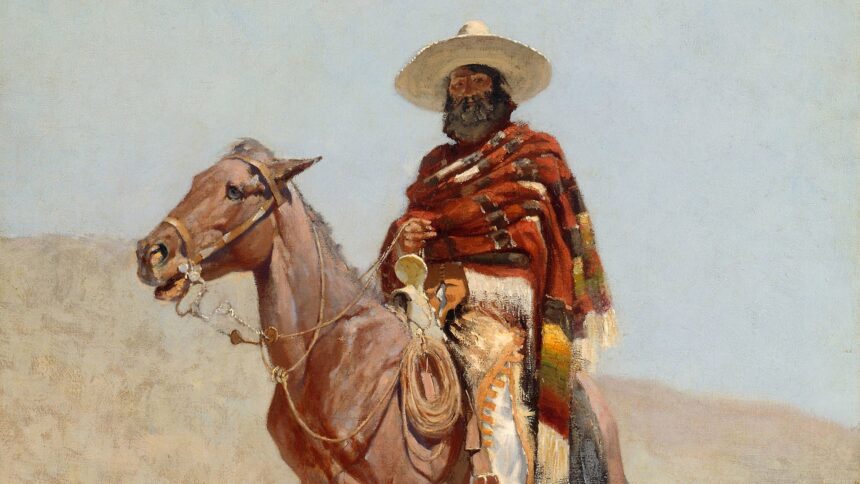

“Cowboys Roping a Bear,” painted by James Walker, c. 1877, SHOWS SPANISH VAQUEROS ROPING A BEAR.

Like the cowboys of American popular culture, the majority of vaqueros were young single men who could handle the grueling and skilled work and could travel where their ranch employers required them to go. As the role of the vaquero developed in New Spain, so did a unique culture—several aspects of which continue to this day. “People that don’t know anything about cowboys would still recognize lassos and chaps,” says Rangel of the vaquero legacy.

Derived from the Spanish word lazo (“rope”), the term lasso was coined in the early 19th century. Originally made with twisted leather hide and horsehair, the lasso “was what really separated [the vaqueros] from the rest of the horsemen that we’d seen,” says Rangel. Skillfully handling a lasso allowed vaqueros to both hunt and rope in wayward cattle. Having workers who could successfully herd cows was particularly important in Spanish missions in what is now California. Cattle provided a crucial source of foodstuffs for the remote mission outposts around which California’s cities later grew.

The West’s rough terrain also led to the development of chaps, the leg coverings vaqueros wore. Originally known as Chaparreras in Spanish, the word is rooted in the word for chaparral, the name for the thick thorny bushes and small trees that are a mainstay of the southwestern landscape.

Vaqueros’ legendary lasso work also helped reshape American entertainment. The vaqueros are credited for creating the elaborate lassoing tricks and roping competitions that would later become the foundations of the first rodeo.

The American Cowboy Rises; the Vaqueros Legacy Remains

Buffalo Bill Wild West Show, c. 1900.

The Mexican vaqueros who helped build the American West were considered such an essential part of the region’s history that Buffalo Bill Cody helped make them famous with his touring Wild West Shows—which portrayed a highly romanticized version of Westward expansion. But it wasn’t until the rise of the film industry that the popular perception of cowboys became one of the white single man who was consistently the hero of the story.

“That’s when the vaquero turns into something else,” says Rangel. “He becomes this racialized, vilified character.” When Latinos and Indigenous people were portrayed in films, they were usually scripted as villains or relegated to the background. Instead, the cowboy became the ideal American male who served as a protector and leader.

Even though vaqueros were sidelined by pop culture and many historical accounts of the West, the ranching methods they perfected endure, with most ranches still incorporating their methods. “The legacies and traditions of the vaquero exist today in modern day rodeo and ranching,” Rangel says. “If you look at how ranches work in places like Texas and even western Nebraska today, you can see that vaquero culture still exists. And vaqueros, or Mexican cowboys, are still doing this work.”