Four days after state officials began transporting huge tents and trailers to build “Alligator Alcatraz,” a 1,000-bed immigration detention center in the Everglades, environmental groups filed a lawsuit to halt the project.

Friends of the Everglades and the Center for Biological Diversity, which filed the lawsuit June 27 in U.S. District Court in Miami, are suing the Department of Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Florida Division of Emergency Management and Miami-Dade County. Friends of the Everglades is represented by Earthjustice and attorneys Scott Hiaasen and Paul Schwiep.

They also filed an expedited motion seeking a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction in an effort to prevent its opening July 1.

“The site is more than 96% wetlands, surrounded by Big Cypress National Preserve, and is habitat for the endangered Florida panther and other iconic species,” Eve Samples, executive director of Friends of the Everglades, said of Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport in Ochopee.

“This scheme is not only cruel, it threatens the Everglades ecosystem that state and federal taxpayers have spent billions to protect. Friends of the Everglades was founded by Marjory Stoneman Douglas in 1969 to stop harmful development at this very location. Fifty-six years later, the threat has returned — and it poses another existential threat to the Everglades,” she added.

During a June 27 interview on “Fox & Friends,” Gov. Ron DeSantis said his administration will defend the detention center in court.

On June 30, Miami-Dade County responded to the lawsuit, arguing there was no basis for the environmental groups’ argument that it could have stopped the detention center through its Comprehensive-Development Master Plan.

“It would be like seeking to constrain the federal government by invoking state law,” Miami-Dade County wrote in its response.

The response noted County Mayor Daniella Levine Cava responded to the Florida Department of Emergency Management’s letter of intent, which outlined the detention plan, by addressing matters concerning the property appraisal, public safety, security — and seeking additional information and details, “particularly regarding environmental safeguards.”

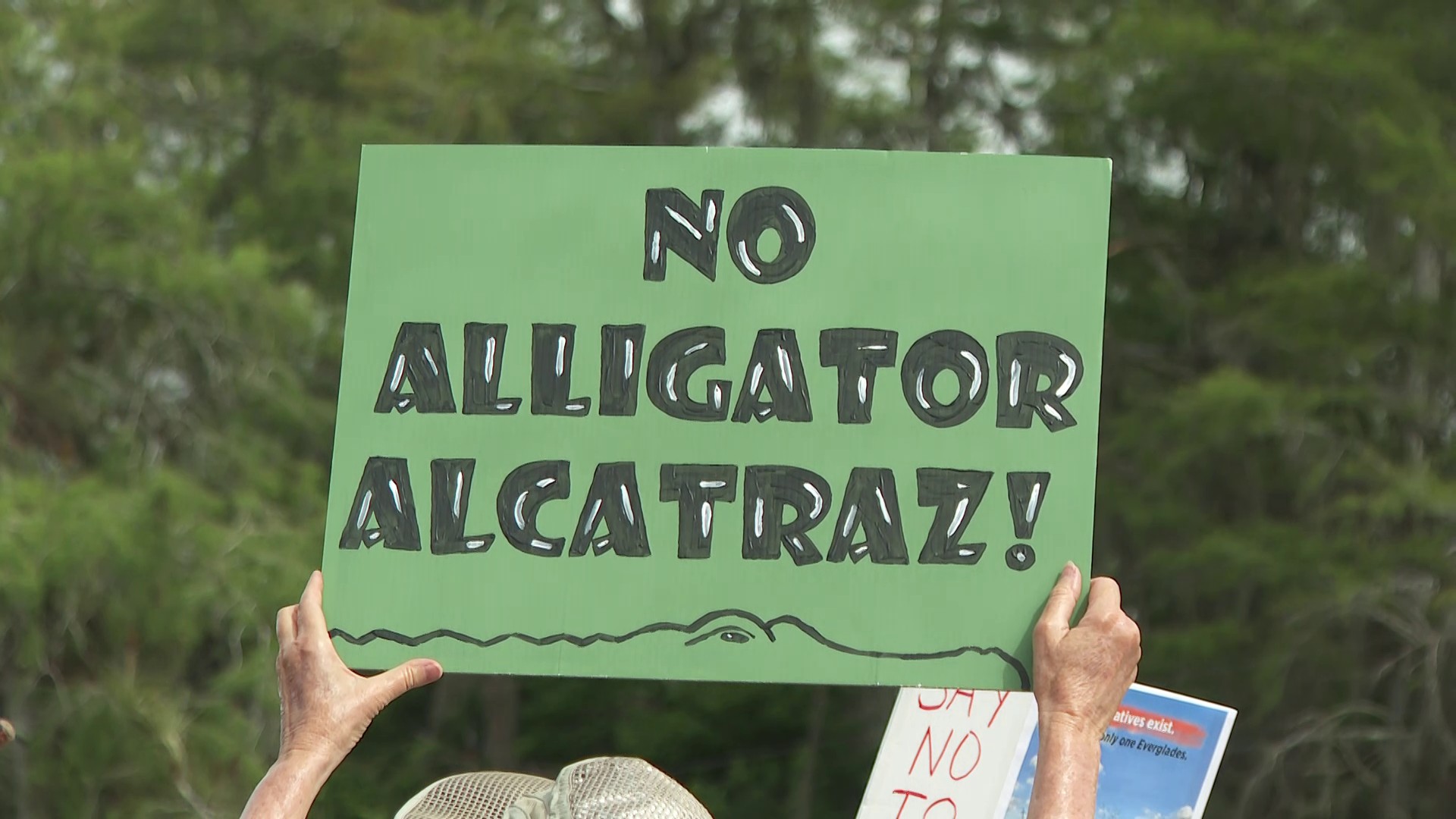

Just as they did a week ago before heavy duty tents, trailers and equipment arrived on–site, Native American Everglades environmental activist Betty Osceola, Love the Everglades and Friends of the Everglades held another protest, standing along Tamiami Trail holding signs, some wearing Indigenous clothing. Motorists drove by honking in support as large trucks rumbled in and out of the property and State Police stood by. “Keep Florida Wild,” one sign said, while others urged: “No ICE in the Everglades” and “Defend the Sacred”.

Environmentalists stopped airport before

Environmentalists stopped airport before

The Everglades Jetport, located in Collier County on 24,960 acres owned by the Miami-Dade Aviation Department, was envisioned in 1968 as an expansion of Miami International Airport to handle upcoming supersonic jets and become the world’s largest airport. One 10,499-foot runway out of six was built, along with a parallel taxiway and administration building. Plans also included a 1,000-foot-wide corridor linking it to both coasts with a new interstate highway and monorail high-speed mass-transit system

In 1969, Florida’s first environmental-impact study, conducted by federal officials, scientists, conservationists and others, showed it would “inexorably destroy the South Florida ecosystem and thus the Everglades National Park.” Work was halted in 1970 by Everglades Jetport Pact.

Only 900 acres of the property is developed and operational, according to the airport’s website, which says the rest — marsh land — is managed and operated by the Florida Game and Freshwater Fish Commission. Since the expansion was halted, it says, there was a $3.2 million runway overlay and lighting upgrade in 1992 and a $100,000 taxiway rejuvenation in 1996.

It’s 6 miles north of Everglades National Park and about 36 miles west of Miami’s business district. The airport is used as a landing and training facility for commercial pilots, private training and some military touch-and-goes, according to the website, which says commercial jet aircraft and military operations regularly use it and there are roughly 175,500 operations yearly.

Plan revealed on podcast

Plan revealed on podcast

The ICE detention center is part of a 37-page immigration-enforcement plan state officials revealed May 12, which they hope will be a national model for President Donald Trump’s mass deportation plan. State Attorney General James Uthmeier first proposed “Alligator Alcatraz” during a June 19 podcast and called it a “virtually abandoned facility.”

“If people get out, there’s not much waiting for them, other than alligators and pythons,” Uthmeier said. “Nowhere to go, nowhere to hide.”

At the time, many thought he was joking.

Collier officials were unaware the plan had moved forward until June 23, the day work began at the 39-square-mile airport. FDEM conducted a site visit in February for “advanced emergency planning,” but Collier wasn’t included in discussions.

County Emergency Services Director Dan Summers told commissioners June 24 he was “taken a little off guard” when work began a day earlier because they never received a “courtesy call.” He said the state will handle on–site emergency services, including fire and emergency medical services.

State emergency

The rapid construction has sparked debate over DeSantis’ authority and definition of a state emergency.

Initially planned for 1,000 beds, state officials later expanded it to 5,000 beds on–site, where heavy duty tents, mobile trailers, kitchen facilities, restrooms, diesel generators and lighting now stand. The runway will be used to receive and deport ICE detainees.

FDEM funds will pay for a portion and state officials say it will cost about $450 million to operate annually, partly reimbursed by the federal government. This week, when the first detainees were to arrive, the National Guard was called on to assist.

The lawsuit alleges the proposal didn’t undergo environmental reviews, as required under federal law, and the public had no opportunity to comment. Despite that, the groups say DeSantis “plowed ahead” with retrofitting the airport into an ICE detention center.

Collier County Sheriff’s Office declined to comment about the project, but said the county jail currently has 145 inmates who are in the country illegally, the same number as last year.

Environmentally sensitive, sacred Indigenous land

The Everglades is the largest mangrove ecosystem in the Western Hemisphere, the largest continuous stand of sawgrass prairie and the nation’s most significant breeding ground for wading birds.

“This reckless attack on the Everglades — the lifeblood of Florida — risks polluting sensitive waters and turning more endangered Florida panthers into roadkill,” said attorney Elise Bennett, the Center for Biological Diversity’s Florida director. “It makes no sense to build what’s essentially a new development in the Everglades for any reason, but this reason is particularly despicable.”

In its response, Miami-Dade said FDEM’s letter said state law authorized DeSantis to “utilize all available resources” of the state and local governments “to cope with the emergency,” including the county’s TNT Airport. “The county must also comply with the requirement that local officials ‘use best efforts to support the enforcement of federal immigration law.’ This requirement is subject to severe penalties for noncompliance.”