The Spanish phrase “Yo voté,” meaning “I voted,” varies in translation across dialects. Local organizations in Nebraska are working to reach Spanish-speaking voters ahead of the upcoming election, uniting communities around the shared message.

With 36.2 million Latinos eligible to vote in 2024, up 4 million since 2020, according to the Pew Research Center, the demographic has grown at the second-fastest rate of any major racial and ethnic group of United States voters since the last presidential election.

Some Latino voters face barriers, including language, that prevent them from registering to vote.

Limited Spanish language resources for voters

With 8.5% of people in Nebraska speaking Spanish at home, according to a 2023 American Community Survey, language barriers can be a factor in the low voter engagement according to leaders in civic and media groups. The Nebraska Commission on Latino-Americans, Nebraska Civic Engagement Table, and Telemundo are working to make election information more accessible to Spanish-speaking communities in the state.

The Nebraska Commission on Latino-Americans aims to bridge this gap by hosting civic engagement sessions in both Spanish and English, and sharing bilingual news updates.

Executive Director María Arriaga said areas with larger populations in Nebraska tend to offer better language resources through campaign outreach and bilingual facilitators.

“There is an improvement, but I think the language barrier is a huge problem in many areas,” Arriaga said. “For rural Nebraska, I’m so surprised that many areas had only one person for years interpreting for the whole district because there was no one else that was bilingual.”

An Nebraska counties map displays three ballot graphics in counties – Colfax, Dakota and Dawson – that require Spanish ballots based on federal criteria of the percentage of voting-age citizens who speak the language. The largest communities of Hispanic populations in these counties are Schuyler, South Sioux City, and Lexington.

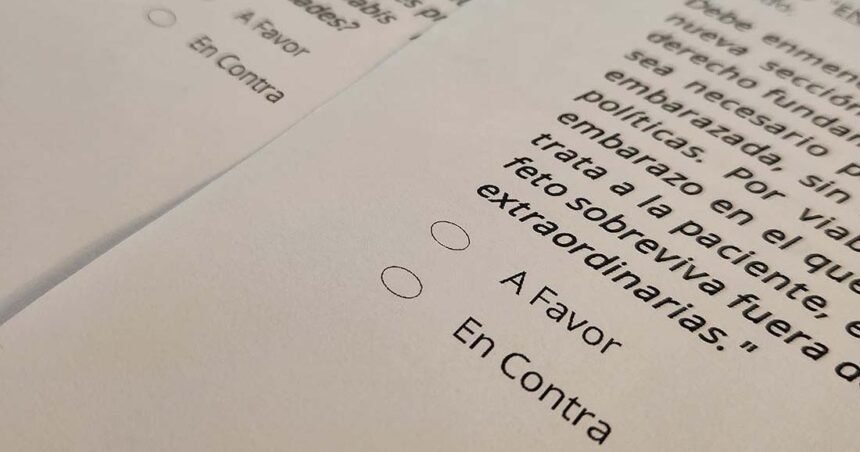

Three Nebraska counties of Colfax, Dakota and Dawson meet federal criteria requiring ballots to be available in Spanish, based on the percentage of voting-age citizens who speak the language.

Larger areas like Omaha and Lincoln, Lancaster and Douglas counties do not meet these thresholds, leaving voters without a Spanish ballot option.

“I think it’s a necessity that is increasing, and it’s if it’s not happening right now, it’s going to happen very soon, because the Spanish language is not going to be decreasing,” Arriaga said. “It’s going to be the opposite.”

Bilingual outreach tackles voter education needs

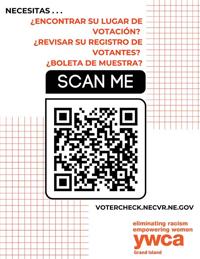

A voter check form in Spanish provides a QR code with information about polling places, voter registration and sample ballots provided by Laura Gamboa Urrego, Greater Nebraska Community Organizer with YWCA of Grand Island. Gamboa Urrego provides this QR code to guide and educate Spanish-speaking voters with the necessary election-related information.

The need for Spanish-language resources is also supported by Laura Gamboa Urrego, Greater Nebraska Community Organizer with YWCA of Grand Island. Through her work with the nonprofit Nebraska Civic Engagement Table, Gamboa Urrego said she understands the limitations of Spanish ballots and runs bilingual voter education sessions.

“I can show them their ballot. I tell them, ‘You can take notes when you go to vote, and if you need help to understand the ballot, come to me or one of our education sessions, and we can help explain what these questions mean,’” Gamboa Urrego said. “Unfortunately, there are ballots that can’t be in Spanish, but you are able to take notes when you go.”

Gamboa Urrego has been going door-to-door in communities with low voter turnout and high numbers of underrepresented groups, providing nonpartisan resources and educating residents about the ballot process and issues. She said some people she spoke with were bilingual and she spoke Spanish to explain certain aspects or answer questions.

Bilingual media amplifies Spanish-speaking voter engagement

Another challenge facing Spanish-speaking voters is the limited availability of unbiased local information.

“In English, it’s super easy to find nonpartisan sources,” Gamboa Urrego said. She said unbiased information in Spanish is more available federally, but doesn’t receive the same attention at a local level. “There’s barely any information out there in Spanish, and that’s a problem. How can our community make an educated choice when we can’t even find the information in our own language?”

As the state’s first network affiliate to offer local news in Spanish, Telemundo Nebraska plays an essential role in providing accessible and accurate information for Spanish-speaking voters.

“Our role is huge and especially with the intensity that we’ve seen in these campaigns,” said Natalie Sáenz, a bilingual journalist at Telemundo. “These Spanish-speaking individuals, who do they turn to? They’re going to turn to the news organizations that they trust. Bilingual news organizations, or just Spanish-speaking organizations, really need to step it up because everything is hitting us on all sides.”

Born in Scottsbluff, Sáenz said she saw a lack of Spanish-language resources while growing up in the area, motivating her to pursue a bilingual media career. She and her colleagues now work to address that gap by covering election issues, explaining local laws, ballot measures and national news that impact the Nebraska community.

“Politics is hard. Understanding the government and the legislative sessions here is challenging,” Sáenz said. “Being able to break that down, and knowing that there are people that look like us, is also very important.”

The future of the vote amid changing demographics

Sáenz said voter outreach to Latino communities appears more intense compared with the 2020 election cycle, locally and nationally.

“We are in a very sensitive moment where a lot of these topics are pretty direct to target the Latino life,” Arriaga said. “Latinos need to be aware that we need to be voting because our vote has a weight. I don’t care who you vote for. We just want the Latino vote because that is going to be affecting every decision, not just the federal level, but a state level as well.”

This year’s campaigns are seeing increased interest from young, first-generation Latinos, according to Sáenz’s observation, some are encouraging their families to vote. At a recent Tim Walz rally in Nebraska, Sáenz spoke to a young Hispanic man who shared that it was his father’s first political rally.

“That is another push that we’re seeing, that big shift in younger generations, really making sure their voices are heard, but also their family members’ voices are heard,” Sáenz said.

Arriaga echoed a similar observation of younger generations becoming more interested in civic engagement, particularly in Lincoln, and said poll data for the upcoming election will provide more information on voter turnout.

Sáenz, Arriaga and Gamboa Urrego said diverse representation in civic spaces can encourage voters and still has room for improvement.

“We want to see more Latinos at every table, in every discussion because if you don’t see people like you involved there, you are going to feel discouraged to do so,” Arriaga said.

She said a wave of politically diverse Latino involvement, even with language barriers, could encourage more thoughtful decision making at every level of governance.

As Nebraska’s Latino and Spanish-speaking population becomes more visible in civic and political spaces, organization leaders say the engagement brings more voices to be heard and represented.

“Everything will change and for good because it’s not just about Latinos; it’s to understand the diversity of Nebraska,” Arriaga said. “You have to learn how to listen to other voices, even when they are not speaking in your same language.”