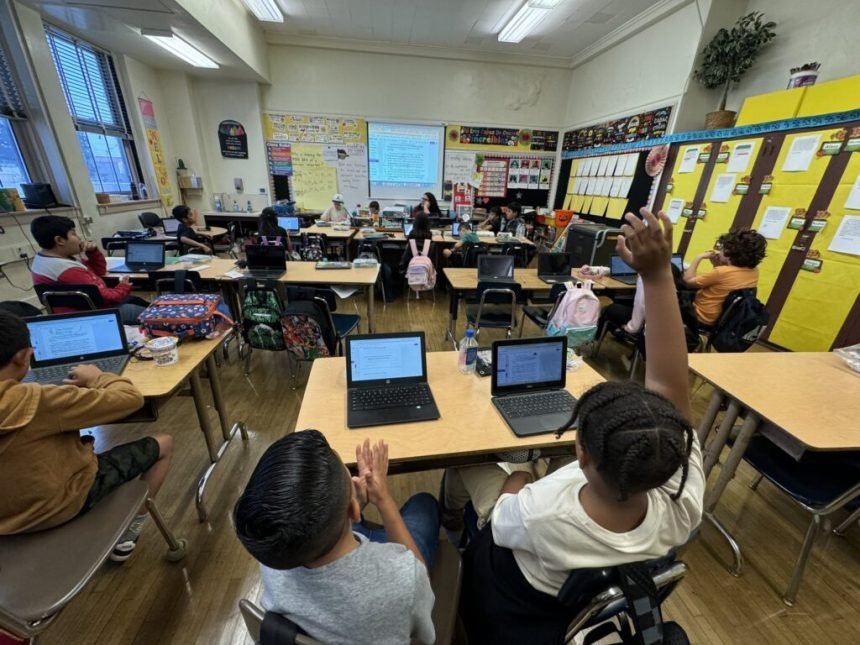

Students in a Los Angeles Unified School District classroom.

Credit: Los Angeles Unified / X

Top Takeaways

- The 1776 Project Foundation filed a lawsuit against the Los Angeles Unified School District, claiming it discriminates against white students.

- The lawsuit is part of a larger trend — both nationally and in Los Angeles.

- Experts say this suit has a better chance of moving forward in the current political climate.

A lawsuit filed against the Los Angeles Unified School District for allegedly discriminating against white students could move forward, given the current political climate. But critics say it is troubling and lacks merit.

The suit by the 1776 Project Foundation takes aim at the district’s Predominantly Hispanic, Black, Asian, or other Non-Anglo, or PHBAO, program and claims that “for students who attend non-PHBAO schools, the District provides inferior treatment and calculated disadvantages.” Roughly 70% of LAUSD schools are part of the PHABO program.

“It’s symbolic, it’s troubling, it’s disturbing. It is part of a larger right-wing agenda to shift the focus from centuries of discrimination, exclusion, and denied opportunity to certain groups and to say, ‘look, white students are being treated badly,’” said Tyrone Howard, the faculty director of UCLA’s Center for the Transformation of Schools.

According to the district, PHBAO campuses are required to hold parent-teacher conferences twice a year. It also involves smaller class sizes, which also apply to non-PHBAO and magnet programs.

Once we achieve a level playing field, then we can talk about what else needs to happen to achieve an equitable education.

Evelyn Aleman, founder of Our Voice/Nuestra Voz

The suit, filed this week in federal court, also calls out the program for allegedly maintaining a more robust staff and receiving extra points on applications to prestigious magnet schools.

“Students attending non-PHBAO schools are denied and directly blocked from these benefits because of the racial composition of their school attendance zone, which detrimentally impacts the quality of the educational experience and directly damages these students,” the lawsuit alleges.

LAUSD said it cannot comment on the suit as the litigation is pending. But in a statement to EdSource, the district stated that it remains “firmly committed to ensuring all students have meaningful access to services and enriching educational opportunities.”

“I don’t think the district is saying we’re going to help child A more than child B if the playing field is leveled. But, it’s not leveled,” said Evelyn Aleman, the founder of Our Voice/Nuestra Voz, a bilingual parent advocacy group.

“Once we achieve a level playing field,” she said, “then we can talk about what else needs to happen to achieve an equitable education.”

A familiar tale

The lawsuit against LAUSD’s program is part of a national trend of a few law firms searching “to challenge where they think that white students have been disadvantaged by policies that are attempting to address racial inequities,” said Kevin Welner, director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Lawsuits and complaints with a similar premise have been filed or threatened in New York, Massachusetts, Illinois, and elsewhere. And it isn’t the first complaint LAUSD has weathered over equity initiatives in the past few years.

In 2023, the district faced a complaint by the Virginia-based conservative group Parents Defending Education, claiming that Los Angeles Unified’s Black Student Achievement Plan discriminated against students of other races.

In response, LAUSD overhauled the program, stating it would no longer focus exclusively on Black students — and later boosted its funding by an additional $50 million this school year.

Both the lawsuit and complaint alleged violations of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment — each a major milestone in civil rights for Black Americans.

The trend is, in part, tied to a similar push from the Trump administration against policies addressing racial inequities, Welner said, “but it’s mainly tied to the current Supreme Court’s recent decisions that have opened the door to these sorts of lawsuits.”

He said this lawsuit might have been laughed out of court just one decade ago, but he is no longer sure of that, given today’s majority in the U.S. Supreme Court, which he called “both very conservative and very activist.”

Welner noted that groups like the 1776 Project Foundation have taken advantage of precedents recently set by the U.S. Supreme Court, such as barring race-conscious college admissions, “trying to extend them beyond where the court was, at least at that point, and perhaps anticipating that the court will go further.”

There are two pieces relevant to this lawsuit that might make it difficult for the plaintiffs to win their case, he added.

First, the PHBAO policy focuses on students’ attendance at designated schools, rather than on each individual student’s race. Second, the policies this lawsuit alleges are discriminatory are based on a decades-old court order that sought to desegregate L.A. schools.

“Los Angeles, like many large urban school districts, has relatively few White students. We have private schools for the affluent and public schools for poor kids of color. There are a few exceptions in affluent communities,” said Pedro Noguera, dean of the USC Rossier School of Education, in a statement to EdSource.

“Those children generally bring enormous advantages with them that are based on the wealth and education of their parents. The district will never be able to fully compensate for inequality, but the desegregation statute allows them to try.”

Ongoing equity concerns

The program’s class-size reductions have their roots in desegregation efforts of the 1970s. But recent research shows that segregation in Los Angeles schools is on the rise, and greater disparities in resources tend to cause poorer academic outcomes.

Howard, from UCLA’s Center for the Transformation of Schools, said that “the way the lawsuit reads is that there are these swaths of white families who are being treated unfairly because they have higher student-to-teacher ratios. They have less access to resources.”

He has yet to see an LAUSD school facing this particular issue, given the district’s demographics and the segregated landscape across Los Angeles.

“It just kind of starts a conversation that’s really not based in real data and evidence, but it gets people starting to think that something is happening that is actually not happening,” he said.

According to a study published by The Civil Rights Project at UCLA in September, the percentage of intensely segregated schools — or those with at least 90% students of color — has grown in Los Angeles from 49.2% to 76.5% between 1988 and 2022.

As a Black student, I’ve seen how efforts to advance equity in our schools have made a real difference for students of all backgrounds, not just one group.

Mariyah, a senior at San Pedro High School

While the lawsuit claims that students in non-PHBAO schools are denied smaller class sizes, Aleman noted that some of the district’s gifted programs, for example, also have smaller class sizes — and often don’t include a large percentage of Black or Latino students.

“As a Black student, I’ve seen how efforts to advance equity in our schools have made a real difference for students of all backgrounds, not just one group,” said Mariyah, a senior at San Pedro High School. “We deserve schools that learn from history and invest in students, not policies that take us backwards.”

The long-term impact of this type of lawsuit could be devastating for educational equity, Howard said. And such lawsuits could, for example, lead districts to question current equity-minded programs.

“I think that programs that are designed to help those student groups that have historically been marginalized will be under scrutiny, may be cut, may be reframed, might be reimagined where they lose some of their original intent,” he said.