In the APSA Public Scholarship Program, graduate students in political science produce summaries of new research in the American Political Science Review. This piece, written by Raymundo Lopez, covers the new article by Amanda Sahar d’Urso, Georgetown University, “What Happens When You Can’t Check the Box? Categorization Threat and Public Opinion among Middle Eastern and North African Americans”.

Why the Census Matters

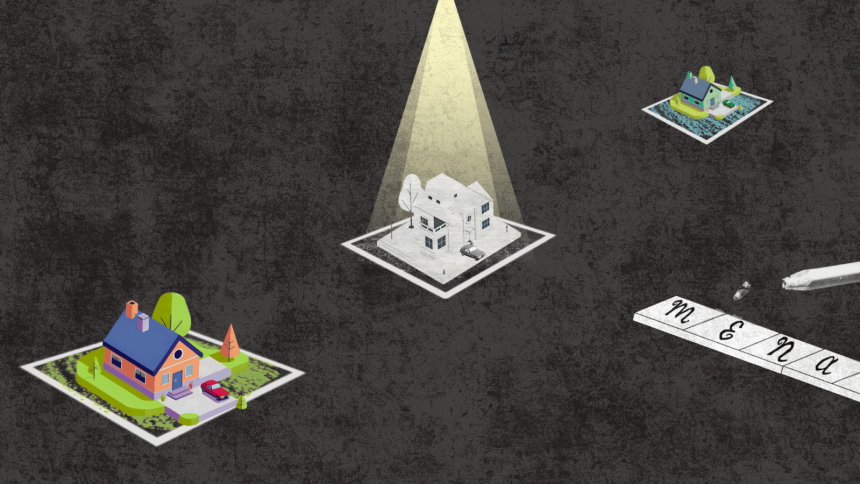

Every year, US Census Data is used to guide the distribution of trillions of federal dollars to state, local and tribal governments. Population data from the Census matter because they directly support public goods like transportation, public health, housing and more. Because different communities have different needs, the Census asks residents to describe themselves using official identity categories in the form of check boxes. Now, imagine filling out the Census and discovering that none of the identity options reflect who you are. What if there’s no box for you to check?

What are the Consequences of Excluding MENAs?

For nearly 50 years, Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) Americans were legally categorized as “white.” Georgetown’s Dr. Amanda Sahar d’Urso argues that this institutional exclusion induces categorization threat—a form of identity denial that shapes how MENA Americans see themselves and engage in politics.

While one might assume that the types of questions we fill out in government forms are insignificant, d’Urso shows us that they carry real psychological and political weight. Her research demonstrates that identity categories are not mere bureaucratic checkboxes—they influence whether people feel recognized and how they express political opinions.

Three Studies, One Clear Pattern

To measure how exclusionary and inclusionary labels shape how MENA Americans think about belonging, d’Urso considers a series of experiments and in-person interviews. Together, these studies reveal a remarkably consistent story.

The two experiments surveyed online respondents of MENA descent to examine how the presence or absence of the “MENA” option shapes how they react to political questions.

“A missing box on a form may seem harmless but for an estimated 3 million MENA Americans, its absence shapes how they feel recognized in this country—and how they experience belonging in our world.”In the first study, some participants were shown a race question with a “MENA” option, while others were not. She finds that when the “MENA” category was missing, MENA respondents asserted their identity in other ways, especially when answering questions tied to their community.

Her second experiment follows the same logic as the first study but strengthens the design in several ways. Using a new set of respondents, she updated the survey to include additional questions while also replicating the results from the first experiment. Additionally, she strengthened the categorization threat treatment condition by removing the “some other race” option from the study—thereby heightening the experience of identity denial.

Across both experiments, she finds the same core result. When people cannot choose the identity category that matches them, they indicate their denied group identity on other parts of the survey.

Finally, to understand how misrecognition feels on a personal level, d’Urso conducted in-depth interviews with MENA Americans from diverse backgrounds. Across the conversations, participants described feeling “invisible” and frustrated when the “MENA” category was not an option on official forms. d’Urso also uncovers an important pattern of resistance. Many interviewees actively skipped the question altogether or selected “Other” and wrote in their identity as a way to assert who they are.

What the Future Holds

A missing box on a form may seem harmless but for an estimated 3 million MENA Americans, its absence shapes how they relate to political and social life in the US—and how they experience belonging in our world. d’Urso’s research shows us that when institutions miscategorize people, our political data not only distort how we may understand entire communities but also overlook how they participate in political life. A missing box on a form may seem harmless but for an estimated 3 million MENA Americans, its absence shapes how they feel recognized in this country—and how they experience belonging in our world.

Looking ahead, 2030 will mark the first time a “MENA” category is included in the US Census. While this shift offers real reason for optimism, the Office of Management and Budget’s proposed definition collapses a highly diverse set of communities into one single category, overlooking important cultural and geographic differences across MENA Americans.

This tension highlights how difficult—and how necessary—it is to study MENA populations accurately, making d’Urso’s scientific analysis a monumental achievement in the field of political science.