Most peoples of the Southwest engaged in both farming and hunting and gathering; the degree to which a given culture relied upon domesticated or wild foods was primarily a matter of the group’s proximity to water. A number of domesticated resources were more or less ubiquitous throughout the culture area, including corn (maize), beans, squash, cotton, turkeys, and dogs. During the period of Spanish colonization, horses, burros, and sheep were added to the agricultural repertoire, as were new varieties of beans, plus wheat, melons, apricots, peaches, and other cultigens.

Most groups coped with the desert environment by occupying sites on waterways; these ranged in quality and reliability from large permanent rivers such as the Colorado, through secondary streams, to washes or gullies that channeled seasonal rainfall but were dry most of the year. Precipitation was unpredictable and fell in just a few major rains each year, compelling many groups to engage in irrigation. While settlements along major waterways could rely almost entirely on agriculture for food, groups whose access was limited to ephemeral waterways typically used farming to supplement hunting and gathering, relying on wild foods during much of the year.

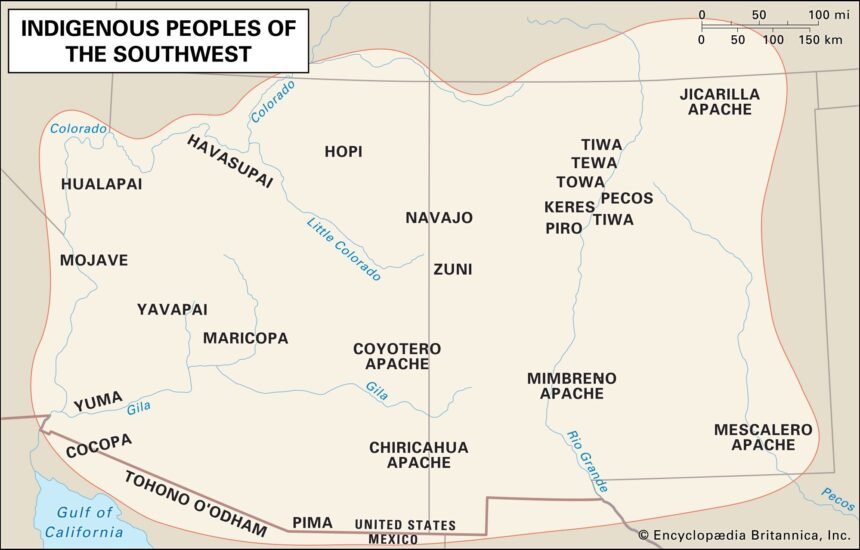

The western and southern reaches of the culture area were home to the Hokan-speaking Yuman groups and the Uto-Aztecan-speaking Akimel O’odham and Tohono O’odham. These peoples shared a number of cultural features, principally in terms of kinship and social organization, although their specific subsistence strategies represented a continuum from full-time agriculture to full-time foraging.

Kinship was usually reckoned bilaterally, through both the male and female lines. For those groups that raised crops, the male line was somewhat privileged as fields were commonly passed from father to son. Most couples chose to reside near the husband’s family (patrilocality), and clan membership was patrilineal. In general women were responsible for most domestic tasks, such as food preparation and child-rearing, while male tasks included the clearing of fields and hunting.

The most important social unit was the extended family, a group of related individuals who lived and worked together; groups of families living in a given locale formed bands. Typically the male head of each family participated in an informal band council that settled disputes (often over land ownership, among the farming groups) and made decisions regarding community problems. Band leadership accrued to those with proven skills in activities such as farming, hunting, and consensus-building. A number of bands constituted the tribe. Tribes were usually organized quite loosely—the Akimel O’odham were the only group with a formally elected tribal chief—but were politically important as the unit that determined whether relations with neighboring groups were harmonious or agitated. Among the Yuman, the tribe provided the people with a strong ethnic identity, although in other cases most individuals identified more strongly with the family or band. (See also The Difference Between a Tribe and a Band.

The most desirable bottomlands along the Colorado and Gila rivers were densely settled by the so-called River Yuman, including the Mojave, Quechan, Cocopa, and Maricopa. They lived in riverside hamlets and their dwellings included houses made of log frameworks covered with sand, brush, or wattle-and-daub. The rivers provided plentiful water despite a minimum of rainfall and the hot desert climate. Overflowing their banks each spring, they provided fresh silt and moisture to small, irregular fields where people cultivated several varieties of corn as well as beans, pumpkins, melons, and grasses. Abundant harvests were supplemented with wild fruits and seeds, fish, and small game.

The Upland Yuman (including the Hualapai, Havasupai, and Yavapai), the Akimel O’odham, and the Tohono O’odham lived on the Gila and Salt rivers, along smaller streams, and along seasonal waterways. The degree to which they relied upon agriculture depended upon their distance from permanently flowing water. Those who lived near such waterways built stone canals with which they irrigated fields of corn, beans, and squash. Those with no permanently flowing water planted crops in the alluvial fans at the mouths of washes and built low walls or check dams to slow the torrents caused by brief but intense summer rains. These latter groups relied more extensively on wild foods than on agriculture; some engaged in no agriculture whatsoever, instead living in a fashion similar to the Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin.

Upland settlement patterns also reflected differential access to water. Hamlets near permanent streams were occupied all year and included dome-shaped houses with walls and roofs of wattle and daub or thatch. The groups that relied on ephemeral streams divided their time between summer settlements near their crops and dry-season camps at higher elevations where fresh water and game were more readily available. Summer residences were usually dome-shaped and built of thatch, while lean-tos and windbreaks served as shelter during the rest of the year.